By Sarah Leavitt

Part of an occasional series on previous and future Museum exhibitions by Sarah, a curator now working from home during the coronavirus pandemic.

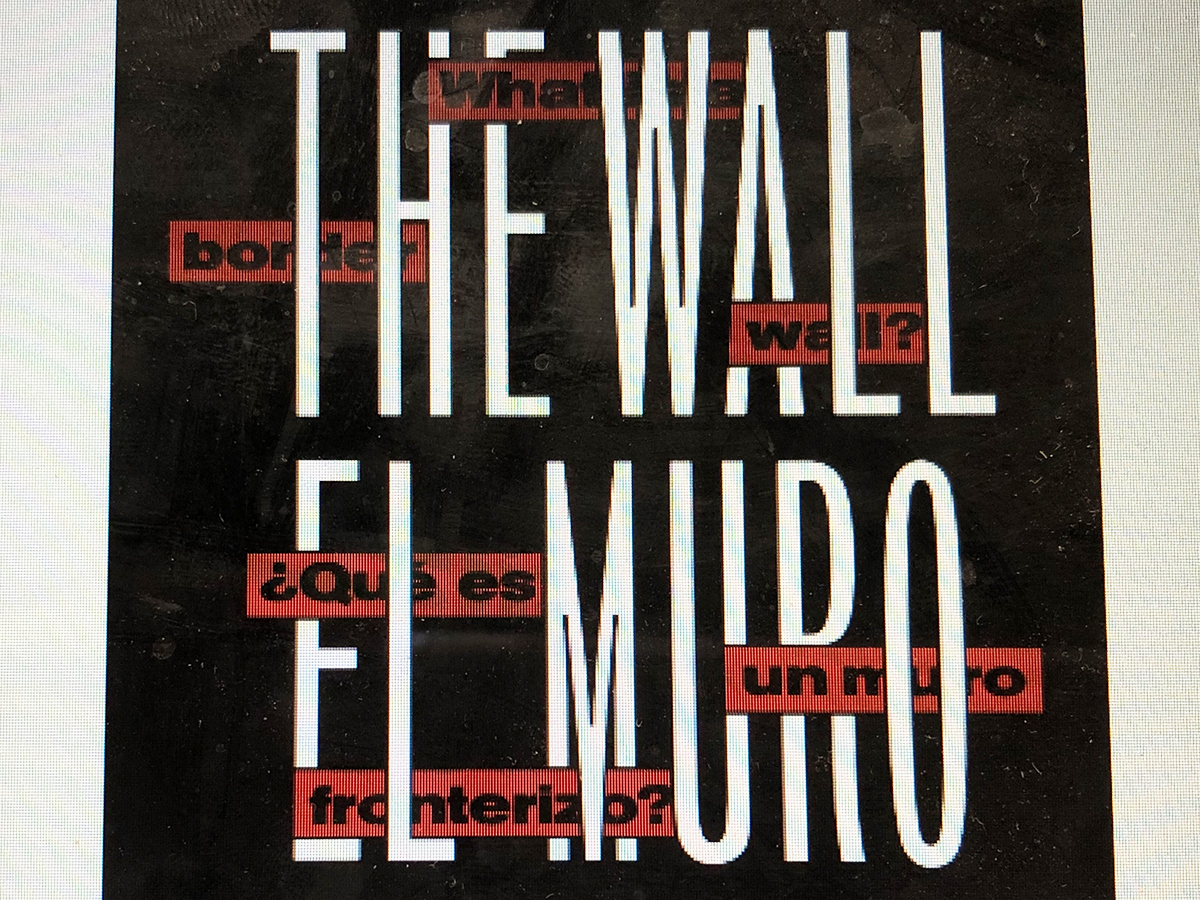

Today is the day an exhibition should have opened. Today, Museum staff should have been mildly panicked, preparing for a press preview of The Wall/El Muro: What Is a Border Wall? I would have been all dressed up. There would have been a table set up with press kits and muffins and coffee, and speeches, and special tours for museum members. I would have been nervous, because I’d have to talk about the exhibition to the public for the first time, and the installation and I would have only just officially met.

There are dozens of exhibitions that should have opened this spring in Washington, D.C. alone, and tens of thousands more across the world. Some of these exhibitions will open later—perhaps in the fall, or maybe next summer. Others, those with complicated international loans or newly unsustainable budgets, will not. With more than 35,000 museums in the U.S., each of which presumably had something planned for spring, the loss for the humanities community is staggering.

The exhibition I’m mourning today is about the border wall between the U.S. and Mexico and, more broadly, about border infrastructure and the history of the nation’s border policy. The text—which I wrote months ago, in a different lifetime—asks us all to think about what borders are, and what they could be. I’ve been working on this show for a few years, during which time I’ve been lucky enough to read extensively, and meet with people who know much more than I do about borders and their ramifications, including our advisory committee. I traveled to the border three times. (Special thanks to Marla Miller, Christina Abuelo, and Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, my intrepid co-travelers, who crossed the border with me from Texas, New Mexico, California, and Arizona, and talked with migrants, border patrol agents, attorneys, and activists.)

This was absolutely not work done in solitude. I hope this exhibition benefited from my involvement, of course, but it truly came together as I listened, read, took notes, and learned from others. For this exhibition, I worked with a phenomenal group of artists and scholars in all different fields, from cartography and architecture to geography, history, and anthropology. To be clear: every exhibition is a team effort, but this team was truly exceptional.

If the exhibition had opened today, and you all came to visit, you would have experienced the beautiful design by mgmt. design and MATTER Architecture Practice, featuring large-scale murals, slats evoking the border wall, and special doorways of contemplation that each ask a “simple” question (such as What is a border? and What is your connection to the border?) for visitors to discuss. There would have been a map of all 66 border walls worldwide by Theo Deutinger, to demonstrate “fixed” borders, and a beautiful animation of the changing location of the Rio Grande by Nicole Antebi, to demonstrate how borders can move. There would have been scale models of the 19th century border markers by Nathan Friedman, an architect in Mexico City, and scale models of the 21st century wall prototypes made—with poured concrete and other materials—by Ane Gonzalez Lara in her Brooklyn studio. In a special “soundscape” gallery, you could have listened to the border at Otay Mesa in the shadow of the wall with Jared Margulies’ installation. You might have picked up a headphone set to hear stories of border crossings from local teenagers, thanks to the beautiful leadership of Joanne Seelig and Imagination Stage.

If the exhibition had opened today, you would have seen a piece of the original border fence once installed at Calexico, California, in 1950, on loan from the National Museum of American History. You’d have seen one of Peter Max’s glorious pop-art signs designed for a land port of entry in 1976, on loan from the General Services Administration. You’d have regarded objects left behind by migrants making their way through the Arizona desert in 2020, on loan from the Undocumented Migration Project at UCLA. You’d have read two versions of a poem that Gloria Anzaldúa wrote in the early ’80s after visiting Border Field State Park in California. (I went there, too, this past November, though I didn’t compose any poetry.) You’d even have had the chance to sit on one of the bright pink teeter-totters that Ron Rael and Virginia San Fratello installed on either side of the border wall in New Mexico last summer.

Maybe you would have disagreed with something you read, or even argued with the text. You might have seen something on a data post (showcasing changes in the numbers of detained migrants, border patrol agents, and miles of wall built, across the past four presidential administrations) that surprised you. You might have paused to really focus on a timeline on the wall, juxtaposing U.S. immigration law with the infrastructure build-up at the border. (Museum curators infamously imagine that visitors will pause to focus on timelines. It rarely happens, but this is all theoretical at this point, so let’s say you would have paused.) At the bottom of the timeline would have been (will be? might be?) one of my favorite parts of the whole exhibition: the “ribbons of fear.” What is it that has led to our changing border policy over time? The timeline showcases our national fears over the past century and a half, ranging from cow tick disease to drug smuggling, to the newer rhetoric about migrant caravans. As these fears have helped dictate policy, I wanted to shine a light on them and bring the conversation out in the open. Another one of my favorite things: the projected animation (designed by mgmt.) that maps the wide reach of border infrastructure across the entire country. The border isn’t just on the border anymore. It never was.

Would you believe it if I said there was more? I don’t want to give it all away; the Museum still plans on installing the show. If The Wall/El Muro had opened today, as planned, I would have given a behind-the-scenes tour and explained the complex provenance of the chain-link fence. I’d have explained the backstory of the photographs I took on my trips, and we could have discussed why I included a bail bonds storefront in El Paso, a dress shop in Nogales, a storage unit in San Diego, and the ICE detention center in Jessup, Maryland, as part of a border infrastructure collage.

This exhibition was the culmination of years of thinking, and talking, and writing—just like every exhibition, I suppose, but this one felt more urgent, more relevant, and more important than anything I’d ever done before in my three-decade museum career. My hope was that visitors would learn about the border in new ways, enabling all of us to read the newspaper, vote, and join the conversation with a clearer, more nuanced understanding of the past and the choices that have led us here. Unfortunately, although the pandemic has slowed or stopped this exhibition, it certainly hasn’t canceled our borders, which continue to be both open (for trade) and closed (for travel, migration, and asylum). The subject of this exhibition, the exhibition I so very much wanted to share with you all, is still relevant and still happening. So many things are delayed, but the virus does not stop at the border, and we can’t (and shouldn’t) stop paying attention.

It is strange to mourn an exhibition that never—or, at least, hasn’t yet—existed. With so many exhibitions that won’t open this spring, after all, I will never know what art I missed out on seeing; what strange new things I might have learned; what culture or society I may have understood more clearly. The loss to the arts world due to all the closed museums, the shuttered theaters, and the muted orchestras is truly incalculable. Beyond the huge numbers in every big-picture analysis, though, is a small exhibition, at a relatively small museum, that perhaps a few thousand people would ever have seen, even in a normal year. But even these are meaningful losses, and even these small exhibitions may have had outsized impacts on the people who engaged with them. This exhibition had an impact on me, and this is the day it should have opened.

Other Essays in This Series

• The Empty Parking Garage

• Kress at the Border

• A Memorial for This Moment

• Thinking About St. Elizabeths