By Sarah Leavitt

Part of an occasional series on previous and future Museum exhibitions by Sarah, a curator now working from home during the coronavirus pandemic.

The last thing you see before crossing into Mexico at the Morley Gate in Nogales, Arizona, is a shopping district. That is not completely accurate, of course, since really the last thing you see is a 20-foot steel bollard fence, or probably a border patrol agent. But before the border patrol, before the razor wire, before the dogs sniffing at your feet, you see a shopping district. I visited Ambos Nogales (“Both Nogaleses”) in January 2020, during a research trip for “The Wall/El Muro,” an upcoming National Building Museum exhibition about the U.S.-Mexico border wall. One of my goals on these trips was to see, hear, and feel, as best I could, the border and its confounding multiplicity of stories.

Most businesses on Morley Avenue on the U.S. side of the border operate almost exclusively in Spanish and sell clothing, perfume, toys, and other discount goods. (I purchased a $1.99 T-shirt that says “MÉXICO” across the front and “18” on the back, for example, though I passed over the fake-diamond-encrusted necklace pendant reading “WIFEY” for $2.99.) There is also a store, Nogales Tactical, that sells camouflage clothing, guns, and other accouterments, catering to the large population of federal border agents who work nearby. There is a local shop, Kory’s, famous for selling wedding dresses to brides on both sides of the border, and another called La Cinderella, both owned by a local Lebanese family. Fewer brides come from Mexico now, even though the store sits literally across the street from the border.

Walking down Morley Avenue toward Mexico, anyone with even a passing interest in architectural history would notice that the discount businesses operate in a downtown built to impress with terracotta flourishes. As in any historic downtown, the buildings in Nogales are clues to what the city looked like a century ago, when it still operated more seamlessly as Ambos Nogales and passage between the sister cities was easier and (maybe?) less fraught. The storefront that caught my eye as I walked from one country to another was Kress, once a familiar five-and-dime store with hundreds of stores across the U.S.

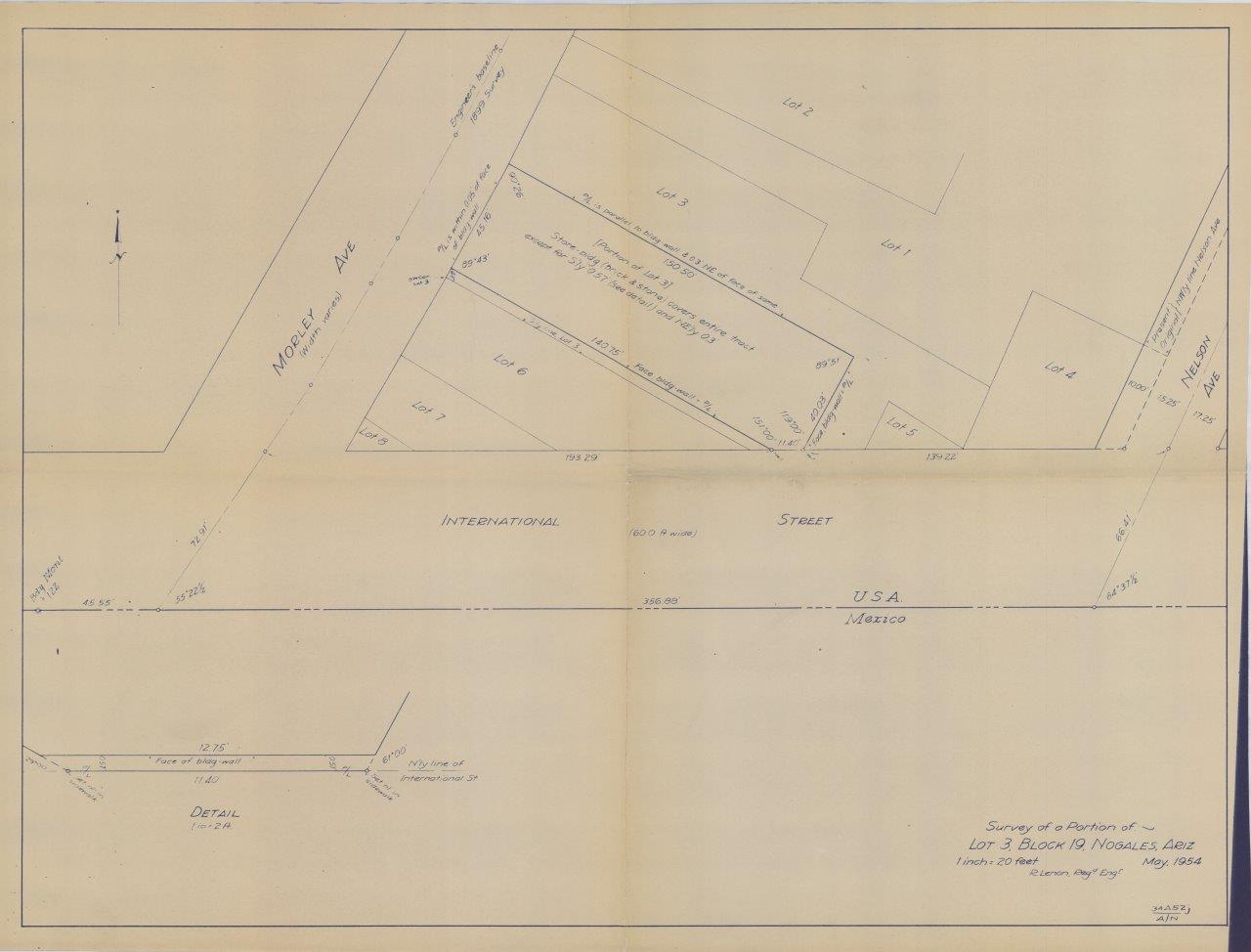

Why Kress? There is also, after all, an old Woolworths on Morley Avenue. But the National Building Museum holds a broad collection of architectural drawings and photographs from S.H. Kress & Company, so my coworkers and I tend to seek out Kress buildings wherever we go. With 50 linear feet of documents, 6,000 architectural drawings, and 7,000 photographs, our collection is the largest documentation of Kress stores nationwide. Most of the collection remains in storage and out of view, even when the Museum is not closed for a pandemic emergency, but there is a Museum project under way to scan the drawings and make this remarkable collection available to the public.

Kress, in business selling affordable goods from 1896 through 1981, was once part of the fabric of many towns throughout America, especially in the South. Even though they are no longer home to this bustling five-and-dime business, these stores embody the history of American retail history and the history of downtown business districts. The company’s architectural division designed stores in a variety of styles from town to town, ranging from Gothic to Art Deco, providing excellent lessons in architectural history. Five-and-dime stores nationwide tell the stories of the 20th century, from desegregation protests at lunch counters in the 1960s to the suburban overhaul of shopping malls, which shuttered many downtown shopping districts in the 1980s. When you see an old Kress store, you’re seeing urban history, familiar in every town, but always different thanks to so many particular, local contexts.

This part of Nogales is still a shopping district, though travel across the border has been harder and harder for people coming north from Mexico. Many locals trace the change to NAFTA in 1994, which altered the trade relationships between the U.S. and Mexico, though the largest transformation came in 2001, when newly strict border enforcement made the necessary documentation more onerous and expensive, and the whole process of running across the border for some cheap clothing or other goods became much less appealing. In many ways, Morley Avenue is a microcosm of border history, with deep connections to retail history, immigration, and the daily life and trade of the towns on either side of the divide.

I only had one day to spend in Ambos Nogales, and therefore have only a passing sense of the town. A friend and I took the time to walk across the border for a margarita at La Roca, an infamous Mexican restaurant, filled with American tourists, and we wandered around the U.S. side, locating the plaque commemorating the first Jewish settler (Jacob Isaacson, 1880) and the park named after a Lebanese immigrant (Nasib Karam). And we shopped (thus the new T-shirt). And we tried to imagine, as well as outsiders can, what it would be like to live, day in and day out, in the shadow of so many bollards and rings of razor wire. There has been a fence in Nogales for 100 years, but this wall, built in 2011, is by far the largest and most imposing barrier.

Amid the sensory overload and heightened experiences of being so close to the border wall, and being watched by so many federal agents with large weapons, the Kress store stands out as a still-standing, though much changed, beacon of a different time. The Kress store reminds me that what is happening at the border now is not the end of the story—that the relationship between these two towns, between our two countries, was once different, and could be different again.

Other Essays in This Series

• The Empty Parking Garage

• Today Is the Day

• A Memorial for This Moment

• Thinking About St. Elizabeths