Documenting Crossroads: The Coronavirus in Poor, Minority Communities

By Camilo José Vergara with Chrysanthe Broikos

ABOUT CAMILO JOSÉ VERGARA

Documenting Crossroads: The Coronavirus in Poor, Minority Communities marks the National Building Museum’s seventh collaboration with Camilo José Vergara. Curator Chrysanthe Broikos and Vergara have worked together previously, most recently organizing Commemorating 9/11: Photographs by Camilo José Vergara, part of a continuing partnership focused on his images of the World Trade Center.

One of the nation’s foremost urban documentarians, Vergara is a recipient of the 2012 National Humanities Medal (awarded by President Barack Obama) and was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2002.

Drawn to America’s inner cities, Vergara began recording New York City’s urban landscape in 1970, the year he settled there. Since 1977, he has systematically photographed some of the country’s most impoverished neighborhoods, repeatedly returning to locations in New York, Newark, Camden, Detroit, Gary, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

Vergara lectures widely and is the author of numerous books and essays. His photographs have been the focus of nearly a dozen exhibitions and have been acquired by institutions nationwide. The Library of Congress will be the permanent home of his photographic archive.

Born in Santiago, Chile, Vergara earned degrees in sociology from the University of Notre Dame (B.A., 1968) and Columbia University (M.A., 1977).

SELECT EXHIBITIONS

Detroit Is No Dry Bones: Photographs by Camilo José Vergara / September 30, 2012–March 17, 2013

Storefront Churches: Photographs by Camilo José Vergara / June 20–November 29, 2009

Twin Towers Remembered: Photographs by Camilo José Vergara / November 10, 2001–March 10, 2002

El Nuevo Mundo: The Landscape of Latino Los Angeles / December 3, 1998–March 28, 1999

The New American Ghetto: Photographs by Camilo José Vergara / January 26, 1996–May 5, 1996

CURATOR ESSAYS

2012: Looking Back, Looking Forward: Notes on Detroit, Deborah Moore Sorensen

2009: Urban Portraiture: The Persona of Place in the Work of Camilo José Vergara, Chrysanthe Broikos

Over the past four weeks (March 8-April 4, 2020), I have been documenting the evolution of poor, segregated communities—in Oakland and Richmond, CA; Newark, NJ; Harlem, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, NY—as they are being affected by the coronavirus. I visited the Bay Area during the second week of March and photographed the West Wind Coliseum Public Market in Oakland, as well as the memorial service for a biker nicknamed Spiderman in Richmond.

But I’ve spent the bulk of my time returning to the busy metropolitan New York City crossroads and transportation centers that I have been documenting for more than a decade:

- East 125th Street at Lexington Avenue, one of Manhattan’s—and Harlem’s—most diverse and energetic intersections.

- The Hub, a crowded, segregated, and ethnically varied shopping district on East 149th Street and Third Avenue in the Bronx.

- Southern Boulevard and Westchester Avenue, the heart of a Latino neighborhood in the Bronx known for its vibrant urban forms, folk art, and fashion.

- Nostrand Avenue and Fulton Street, the cultural center of Brooklyn’s African American and West Indian population.

- Broadway Junction, a busy Brooklyn transfer point for six connected subway lines and buses that line up along Van Sinderen Avenue.

- Roosevelt Avenue from 103rd Street to 74th Street, a 30-block stretch of shops in a segregated section of Queens.

- Newark’s Four Corners, the city’s unofficial town square located just two blocks west of Newark’s Penn Station.

These crossroads are social condensers and amplifiers, yet they are barely mentioned in media depictions of the virus and its impact. They are teeming with people: street vendors, evangelists, shoppers, security guards, school children, people on their way to work or going home, those who come to observe the crowd, and to be observed—as well as the police. Density and diversity render these spots prime locations for observing a host of interactions and behaviors, from shopping habits and fashion trends to familial interactions and health practices. In short, these hubs reveal the precautions residents of these segregated communities are, or are not, taking to avoid being infected by, and spreading, the coronavirus. (This theme is explored in the companion exhibitions Documenting Crossroads: The New Normal, published in late June 2020, and Documenting Crossroads: Survival and Remembrance Under the Pandemic, published in early December 2020.)

© Camilo José Vergara

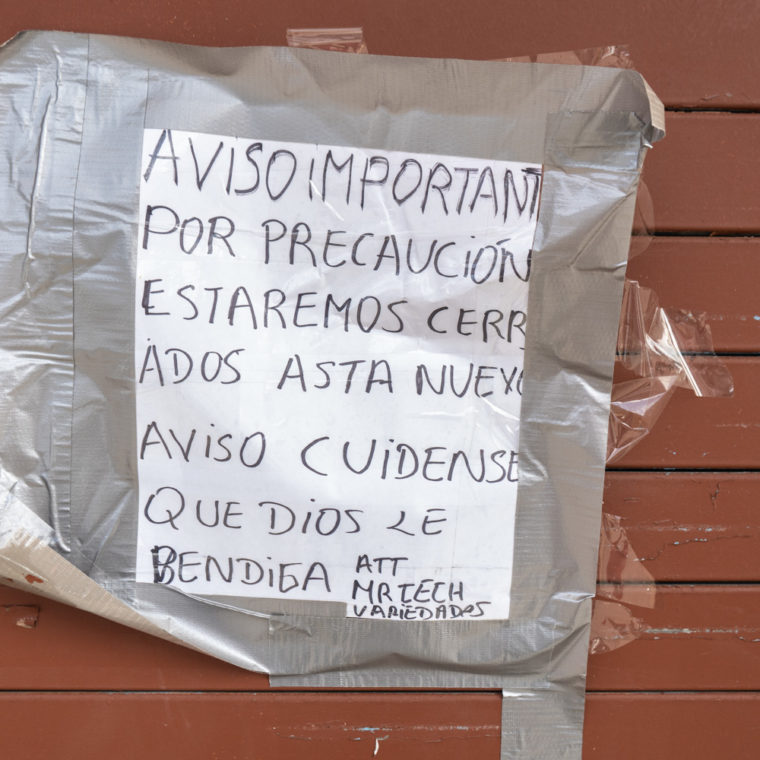

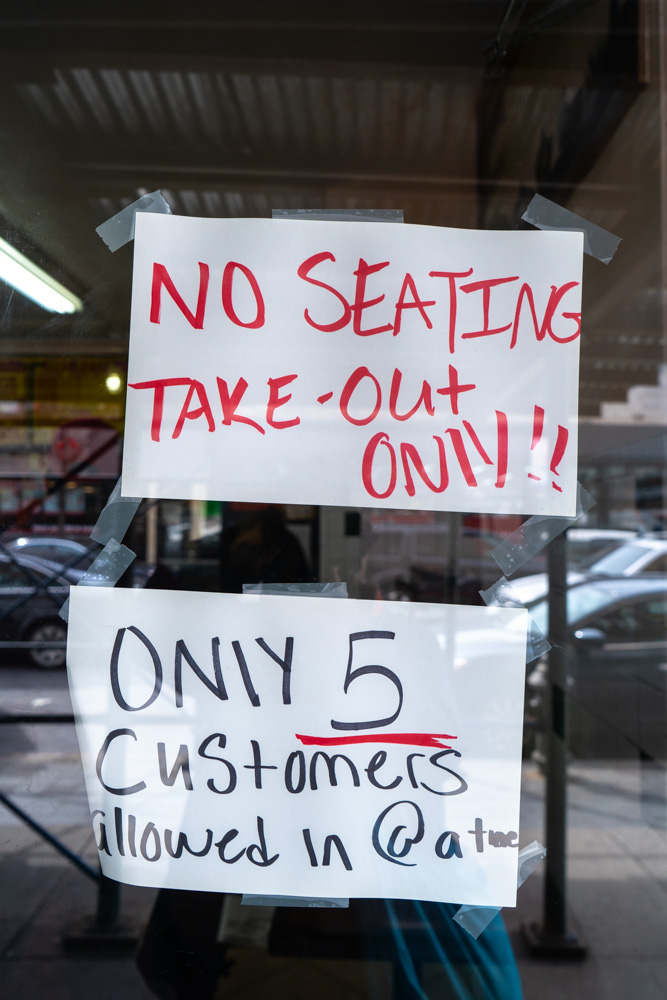

I travel by foot, subway, bus, train, and while in California, by rental car. The most important change I have observed is the growing self-distancing of people from each other on the streets, inside stores and offices, and on subways and buses. Crowds are getting thinner. Protective devices such as masks and gloves are altering the way people dress. Most businesses are shuttered, often displaying hastily written signs explaining to customers that they are temporarily closed. At Ali’s Trinidad Roti Shop on Fulton Street in Brooklyn, now closed, I overheard the cashier firmly telling a customer, “You can’t come in, only five people can come in, otherwise I get a ticket.”

Until just recently, income tax preparers, barber shops, tattoo parlors, botanicas, and pawn shops were open for business. Today, liquor stores, check cashers, gas stations, laundromats, medical offices, and florists are still. Joseph, who was planting flowers at Roberto Clemente Plaza in the Bronx, told me, “The governor made us essential workers.” I saw a sign at St. Luke’s Catholic Church in the Bronx that read “Practicas del Via Crucis,” asking parishioners to attend tryouts for Good Friday services on April 10.

I’ve overheard touching sentiments on my rounds. In Times Square, a man on his cellphone pleaded, “Stay safe somehow, all right, baby?” In the Bronx, one man told another, “I got paid today. My buddy just got laid off.” And in Jackson Heights, on Roosevelt Avenue, a woman on the phone was clearly trying to convey what she felt were her more important worries to a loved one: “Alla en El Salvador le van a dar un balazo [There in El Salvador, he is going to get shot].”

I’ve watched people entering Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx reach for the door with disposable gloves on, winter gloves, with their sleeve, or just a tissue to avoid touching the door with their bare hands. We are all starting to notice, or perhaps just say things, we never did before. A woman on the subway told me that my nose was running and asked me to wipe it. As a passenger boarded a shuttle bus to Harlem, a young man exclaimed, “You f***ing stink and you get on the bus. Take a shower, there are lot of places where you can take a shower. Oh my god, you smell.”

“Stay home” or “shelter in place” rings hollow for large numbers of New Yorkers, especially those who make their living on the streets. Some panhandlers, for example, are becoming more aggressive. They are getting closer to people and more insistent. In Times Square, a man said, “Why are you looking at me like that? Why are you looking at me like that, nigger? I saw you looking at me.” I quickly left.

In Manhattan’s 96th Street Station, a seemingly insane homeless woman hollered and then laughed, while two policemen watched. She eventually got on a train with two large bags and left. One week ago, at Broadway Junction Station in Brooklyn, a man at the top of an escalator was screaming, “I am not moving for f***ing nobody.” Five police officers intervened, gently asking, “What do you need help with?” He responded by calling them “nigger clowns,” then walked away and boarded the subway to Manhattan.

Based on my experience, police seem reluctant to directly intervene in situations such as these. Rather than pursue a possible arrest, they are more inclined to move an individual along. Officers are not acting alone when approaching people, but are standing close to each other in groups of two or more, as if the contagion were only being spread by civilians, not from their fellow officers.

On Willis Avenue in the Bronx, I hear one man tell another, “This is a serious time. The tourists are gone, the restaurants are closed, the bodegas are open until 8:00 pm, and this guy is president. The violence is coming.” Similarly, on Fulton Street in Brooklyn, an elderly man tells me, “The virus is spreading, and the attitude is growing.”

On my way home one afternoon, I noticed the subway stations screens flashing the words “Solidarity, Respect, Kindness” and a 2020 census advertisement telling us that “We all get to shape our future.” A subway musician reassures riders, “Don’t worry, like all storms, this will blow over.” As spring deepens, the virus is becoming more deadly—especially in the neighborhoods where New York’s already most vulnerable populations live.