The historic home of the National Building Museum was built between 1882 and 1887 for three distinct purposes: to house the headquarters of the U.S. Pension Bureau, to provide a suitably grand space for Washington’s social and political functions, and to commemorate the service of those who fought on the side of the Union during the Civil War.

Before the Civil War, most pensions (money or land grants offered to veterans disabled in the course of military service and to the widows and orphans of officers killed) were paid out by state governments, as many veterans served in state militias, not for the federal government. However, by 1864, of the 51,135 pensioners on the rolls, more than 48,000 had served in the Civil War. By 1871, new claims and new eligibility provisions added over 250,000 new pensioners to the rolls—and the numbers kept increasing. Not only did the Civil War greatly increase the number of pensioners, the war also created a demand for federal workers and office space to administer the pensions. This tremendous growth is what prompted Congress, in 1881, to commission the Pension Building.

U.S. Army Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs was appointed as both the architect and engineer for the building. The building was Meigs’ final and most important architectural work, and the one of which he was most proud.

Upon its completion in 1887, the space accommodated approximately 1,500 clerks and officers who serviced 324,968 Civil War pensioners. In that time, less than 20 years after the war, 890,000 pension claims had been filed on behalf of those killed or wounded in the Civil War (though not all were approved). Pensions made up almost one-third of the federal budget in the 1880s and took up much of the business of the 49th Congress (1885–1887), a group that included many Union veterans. Forty percent of the legislation introduced in the House and 55% in the Senate consisted of special pension acts.

Confederate veterans and their dependents were not eligible for pensions from the federal government until 1958. Many states that had joined the Confederacy, however, did pay out pensions. Pensioners from southern states who were eligible due to their service in other wars—particularly the Indian Wars and the Mexican-American War—were dropped from the federal pension rolls during the Civil War, but reinstated in 1872.

World War I brought many changes to the Pension Bureau, leading eventually to its consolidation with other agencies and its move out of the Pension Building. The Bureau of War Risk Insurance took over administration of some veterans benefits. In 1921, just before the Pension Bureau moved out of this building and 56 years after the end of the war, there were still a half-million Civil War pensioners on the rolls. Of this number, 218,775 were “survivors and invalids,” 102 were nurses, and 281,225 were widows and other dependents.

While the building comfortably housed the pension workers, it also provided space for grand D.C. events, specifically presidential inaugural balls. Grover Cleveland held the first Inaugural Ball in the Pension Building in 1885, despite construction not being complete. A temporary wooden roof was placed on top of the building to keep guests protected from the D.C. winter. Benjamin Harrison’s 1889 fete boasted 12,000 guests and a hot-air balloon attraction. William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft held their balls in the Pension Building, each party more spectacular than the last. The affairs were open to the public, and attendees enjoyed a large meal (if they could score a ticket). For example, for a $1 fare, guests at President McKinley’s ball enjoyed oysters, consommé, lobster salad, pate de fois gras, roman punch, Smithfield ham, and assorted cakes, among a dozen or so other dishes. The day after Roosevelt’s Inaugural Ball, orphans from around the city were admitted inside to enjoy the splendor of the previous night’s decorations.

Planning and decorating for these balls was a lengthy, expensive affair, and after protests against the lost productivity and wages of the Pension Office due to closures surrounding the events, Woodrow Wilson’s administration decided to stop hosting them here. While some presidents still hosted modest get-togethers after being sworn in, the grand balls did not return until well after the Great Depression and World War II. Richard Nixon held six balls, one of which returned to the Pension Building. Jimmy Carter invited 300,000 people to his celebrations, wanting them to be known as the “People’s Inauguration.” By contrast, ticket prices for Ronald Regan’s inaugural event here were then-record high, at $100. George H.W. Bush’s first Inaugural Ball held here (one of 10 throughout the city) was the first under its new moniker of the National Building Museum. Bill Clinton hosted his “Blue Jean Bash,” a celebration with contemporary music, to begin his first term. George W. Bush used his second-term event in 2005 to honor all veterans of the War on Terror, inviting those who served or were about to serve in Iraq to attend as his guest. Barack Obama and Donald Trump have continued the tradition of hosting celebrations here.

Generally, the events hosted here are not ticketed and are reserved for campaign donors, as the President and First Lady are almost always committed to attending. While the National Building Museum is not involved with the planning or ticketing for these events, we are proud to host them as a continuation of the original purpose of the historic building.

In designing Museum’s historic home, Meigs was inspired by two Roman palaces. The exterior is modeled closely on the brick, monumentally scaled Palazzo Farnese, completed to Michelangelo’s specifications in 1589. The building’s interior, with open, arcade galleries surrounding a central hall, is reminiscent of the early-16th century Palazzo della Cancelleria. For the colossal Corinthian columns that divide the Great Hall, Meigs took his inspiration from the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome, built by Michelangelo in the mid-16th century.

Meigs chose to use bricks for their low cost and fireproof qualities, but employed expert bricklayers to achieve the building’s regular, smooth face. An ingenious system of windows, vents, and open archways allows the Great Hall to function as a reservoir for light and air. He also considered the building’s day-to-day functions: the stairs between the first three floors of the building were designed with wide treads and low risers to accommodate wounded veterans who might arrive on crutches. Further, to facilitate distribution of paperwork throughout the office, he designed a metal document track on which a suspended basket of papers, operating via a pulley system, could be ferried around. Dumbwaiters in the northwest corner of the building transported the baskets between floors.

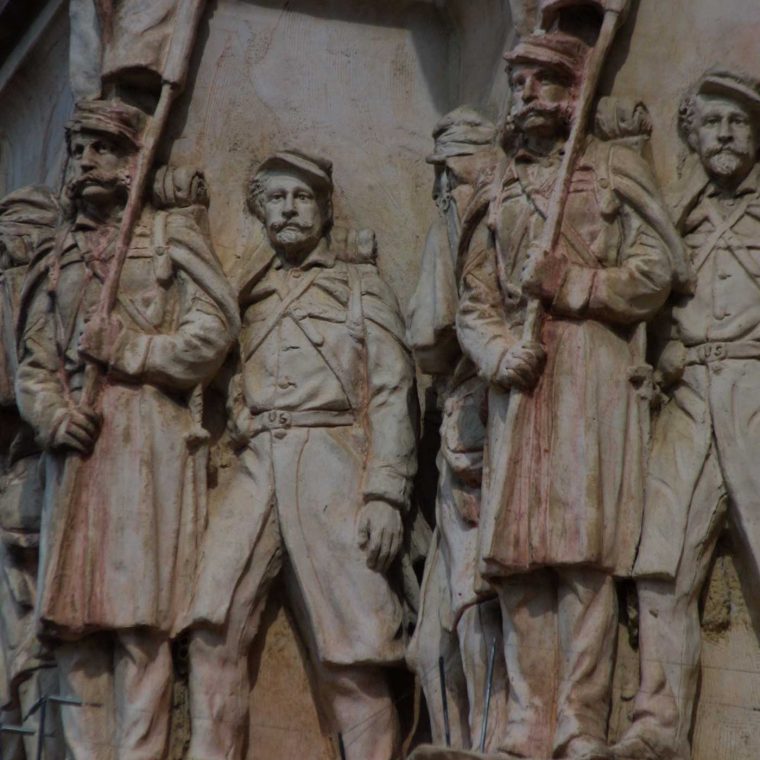

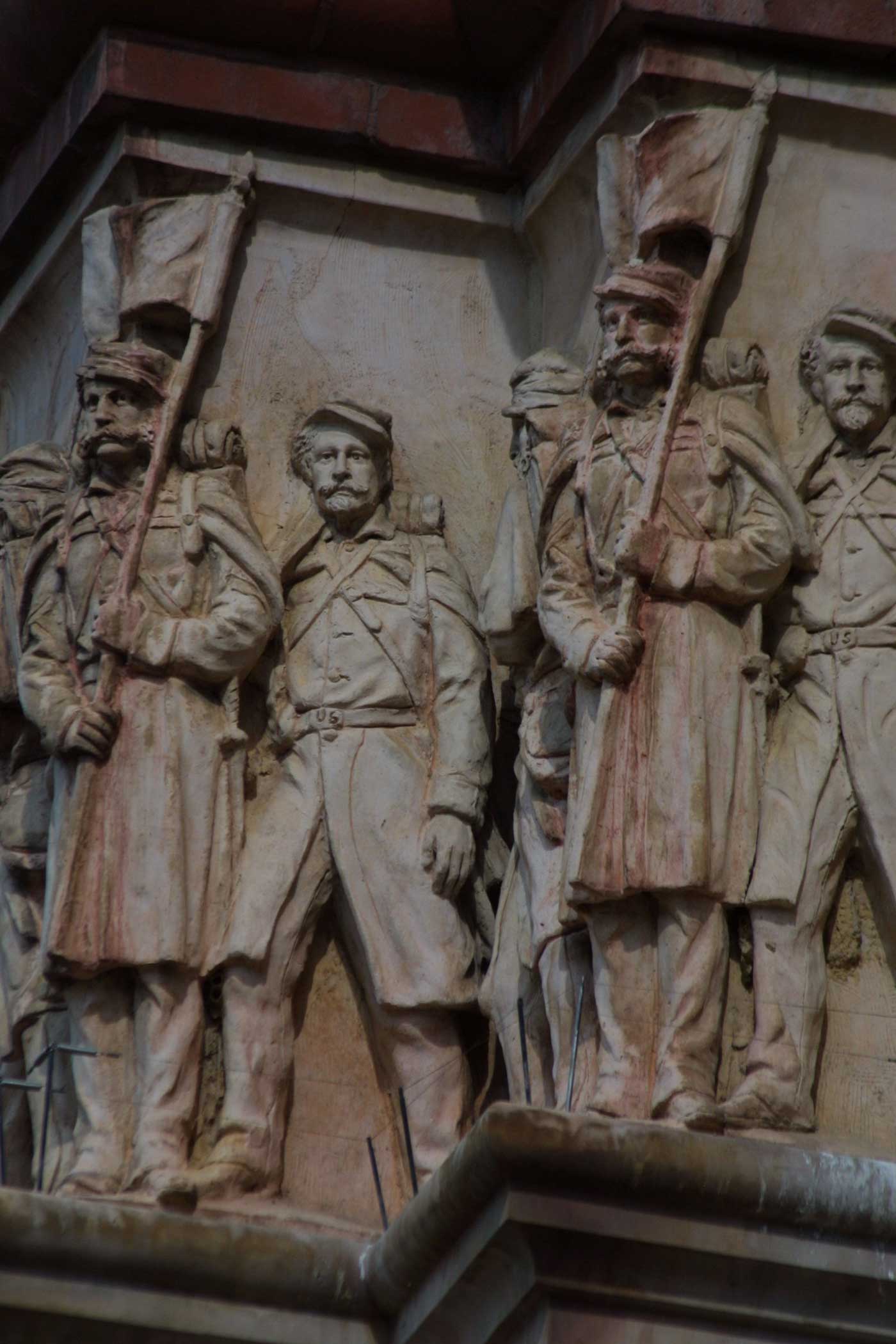

The interior of the building is dominated not by offices and storage facilities, but by a grand central space called the Great Hall. The Great Hall features a central fountain and is divided into three courts by two screens of four colossal Corinthian columns—among the tallest classical columns in the world. A 1,200-foot-long terra cotta frieze on the building’s exterior, designed by Bohemian-born sculptor Caspar Buberl (1834–1899), commemorates the Union infantry, cavalry, artillery, naval, quartermaster, and medical units that fought in the Civil War. The portion of the frieze above each entrance is unique: the western (5th Street NW) entry is the Gate of the Quartermaster, the southern (F Street NW) entry is the Gate of the Infantry, the eastern (4th Street NW) entry is the Naval Gate, and the northern (G Street NW) entry is the Gate of the Invalids.

The Pension Building continued to serve as office space for a variety of government tenants through the 1960s. The government considered demolishing the building as it was badly in need of repair, but then came under pressure from preservationists and commissioned Washington, D.C.–based architect Chloethiel Woodard Smith to explore other possibilities for its use. In her 1967 report, The Pension Building: A Building in Search of a Client, Smith proposed that the building be converted to a museum of the building arts. Her efforts were endorsed by other early supporters such as Dr. Cynthia Field, Herbert Franklin, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Robert Peck, and Beverly Willis. In 1969, the Pension Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Congress passed a resolution in 1978 calling for the preservation of the building as a national treasure, and a 1980 Act of Congress mandated the creation of the National Building Museum as a private, nonprofit educational institution.

After years of careful restoration, the Museum opened its historic home in 1985 with its inaugural exhibition, Anatomy of a Bridge: Seven Steps in Constructing the Brooklyn Bridge, and has presented more than 300 exhibitions since then. It was officially renamed the National Building Museum in 1997.

Original Cost

$886,614.04

Exterior Dimensions

400 feet by 200 feet, 75 feet to cornice level

Materials

15,500,000 bricks with brick and terra cotta ornament

Exterior Frieze

1,200 feet long, 3 feet high, made of terra cotta; features a continuous parade of Civil War military units designed by Caspar Buberl (1834–1899)

Great Hall

316 feet by 116 feet, 159 feet (approximately 15 stories) at its highest point

Corinthian Columns

75 feet high, 8 feet in diameter, 25 feet in circumference; each built with 70,000 bricks and originally painted to resemble marble in 1895

Busts

234 busts designed by Gretta Bader in 1984

Arcade

72 Doric-style columns on the ground floor and 72 Ionic-style columns on the second floor.

We invite you to learn how preservation has guided the transformation of the former Pension Building into the National Building Museum. This program was produced as part of the Museum’s 40th Anniversary celebration week.