By Sarah Leavitt

Part of an occasional series on previous and future Museum exhibitions by Sarah, a curator now working from home during the coronavirus pandemic.

We are going to need a memorial when this is over. Whether that’s next year or—let’s not think about this—even later, once there is a vaccine and the global pandemic has subsided, we are going to need a memorial. What’s more likely is that there will be several.

As I think through the exhibitions I’ve worked on at the National Building Museum within this unexpected context of a pandemic, the drawings and models of the bas-relief sculpture panels from Washington, D.C.’s World War II Memorial keep coming to mind. I’ve been thinking about how we are so familiar with war memorials and the people and values that these monuments represent, while we are perhaps less able to think through what a memorial to those lost to epidemics might look like, or what work it might do to educate future generations.

Certainly, many people probably have never seen a memorial to an epidemic, other than the periodic display of the AIDS Quilt, panels of which were displayed at the National Building Museum in 2012. In fact, however, 2018 was a big year for epidemic memorials, commemorating the century since the 1918 Flu epidemic with, for example, a “reflection bench” at a cemetery in Barre, Vermont, and a memorial at Camp Merritt in New Jersey, a military camp that lost over 500 soldiers to influenza during World War I. These joined several cemetery memorials, including one to the Māori victims of the flu in New Zealand, and a row of memorial trees on University of Montana campus in Missoula. There is also a memorial to the victims of the 1854 cholera epidemic in London—one that also pays tribute to the public health work that solved the mystery of transmission. And there is a memorial to those who died from HIV/AIDS in both Los Angeles and New York City, and plague crosses in honor of those who died in 16th century Europe.

I’m sure there are others, as well, but for sure the number of memorials devoted to epidemics is vastly smaller than those focused on war. This reveals something about priorities; what and whom we memorialize as a nation, and at the state/municipal level as well, is certainly a fascinating and well-traveled subject. (Incidentally, there are also, of course, vast differences in which wars we memorialize in our monument-park-statue landscape. But I digress.)

As we look more closely at the war memorials all around us—often in town squares, on college campuses, and on the grounds of capitol buildings nationwide—we can observe a few things that may help illustrate how this pandemic could be memorialized. One interesting way might be to think about not only the battlefield losses but also the changes and significant events on the home front. As we know to be true during war, and certainly pandemics, vast swaths of people are affected by the global crisis in indirect but fundamental ways. We can see some hints at how an eventual memorial to this pandemic might encompass a wide variety of stories.

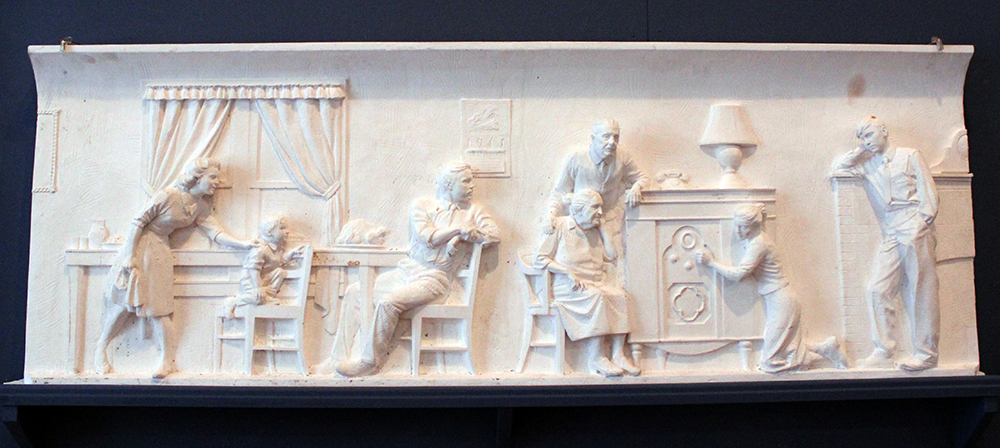

The National Building Museum holds a collection of drawings, photographs, and models from sculptor and architect Raymond Kaskey, who has designed all sorts of memorials, including the World War II memorial on the National Mall. When I worked on a 2014 exhibition of Kaskey’s work, Cool & Collected: Recent Acquisitions, the maquettes of the Home Front panels struck me as particularly important. For tourists visiting the memorial, who might think that it would be limited in scope to honor U.S. military personnel who died fighting overseas, the Home Front panels help to widen the scope of the story the memorial can tell. The bas-relief panels—on one side commemorating the Atlantic Theater and the other side the Pacific Theater—intersperse battle scenes with views of people back home in the U.S. Because they were part of the war effort, too.

Any future memorial to the pandemic will honor those who died, which any proper memorial must do, but I hope it will also pay tribute to all those who tried their best to help each other during the duration. And I hope there is a way to tell the story of all of the efforts on the home front while also acknowledging the ways we fell short, something precious few memorials successfully do. Looking at photos of these World War II panels that we displayed in our exhibition and that also adorn the memorial itself, I am thinking about parallels to today’s crisis. The bond drive has parallels to my neighbors raising money for sanitation workers, collecting masks and other personal protective equipment to donate to our local hospital, and encouraging each other to support local restaurants during this crisis. Just like the bas-relief panel of World War II medics, there should be a place to honor healthcare workers. There are also parallels to the agriculture panel, with the meat-processors, farmers, and grocery store clerks who are on the front lines of our home-based experiences, often not well enough compensated for the daily risks they take. Any future memorial could honor the school children and teachers who tried their best to learn under ridiculous conditions.

If the memorial sculptor is creative and the funders of the memorial are brave, there are ways a future memorial could serve several purposes by honoring the dead and those who helped each other while also recognizing the public health and societal failures endured by many. A memorial could highlight experiences of those who suffered through the pandemic in detention, or recognize the millions of Americans who filed for unemployment in the weeks following the national stay-at-home orders. Just as the World War II Memorial features symbolic eagles, wreaths, and columns, a pandemic memorial could use sculptural symbolism to remind future visitors that often people without proper resources were not protected; that often, we fell short in taking precautions; and that often, people disagreed about how to handle the crisis. When people walk through the World War II Memorial, they are meant to feel a variety of things: pride, sorrow, respect. I hope the memorials we build to the pandemic can offer those things and perhaps also determination to provide better next time for the most vulnerable among us.

And I certainly hope to find a parallel in any future memorial to the bas-relief panel on the World War II Memorial that commemorates the end of the war, as families hear the announcement and could rejoice in the renewed peace. Someday, I hope to be able to stand near that part of a memorial and be thankful that it’s over.

Other Essays in This Series

• The Empty Parking Garage

• Kress at the Border

• This Was the Day

• Thinking About St. Elizabeths