By Sarah Leavitt

Part of an occasional series on previous and future Museum exhibitions by Sarah, a curator now working from home during the coronavirus pandemic.

Just a few weeks after the country shut down due to COVID-19 in early April, I was disheartened to read that there were already cases of the virus at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. A few weeks after that, more than 100 patients were quarantined for probable infection, several patients died, and dozens of staff members tested positive, with additional staff members quarantined. WAMU, the local public radio news station, concluded an April 17 story on the crisis by noting, “St. Elizabeths is the city’s only public psychiatric hospital, and has a long and troubled history in the District.”

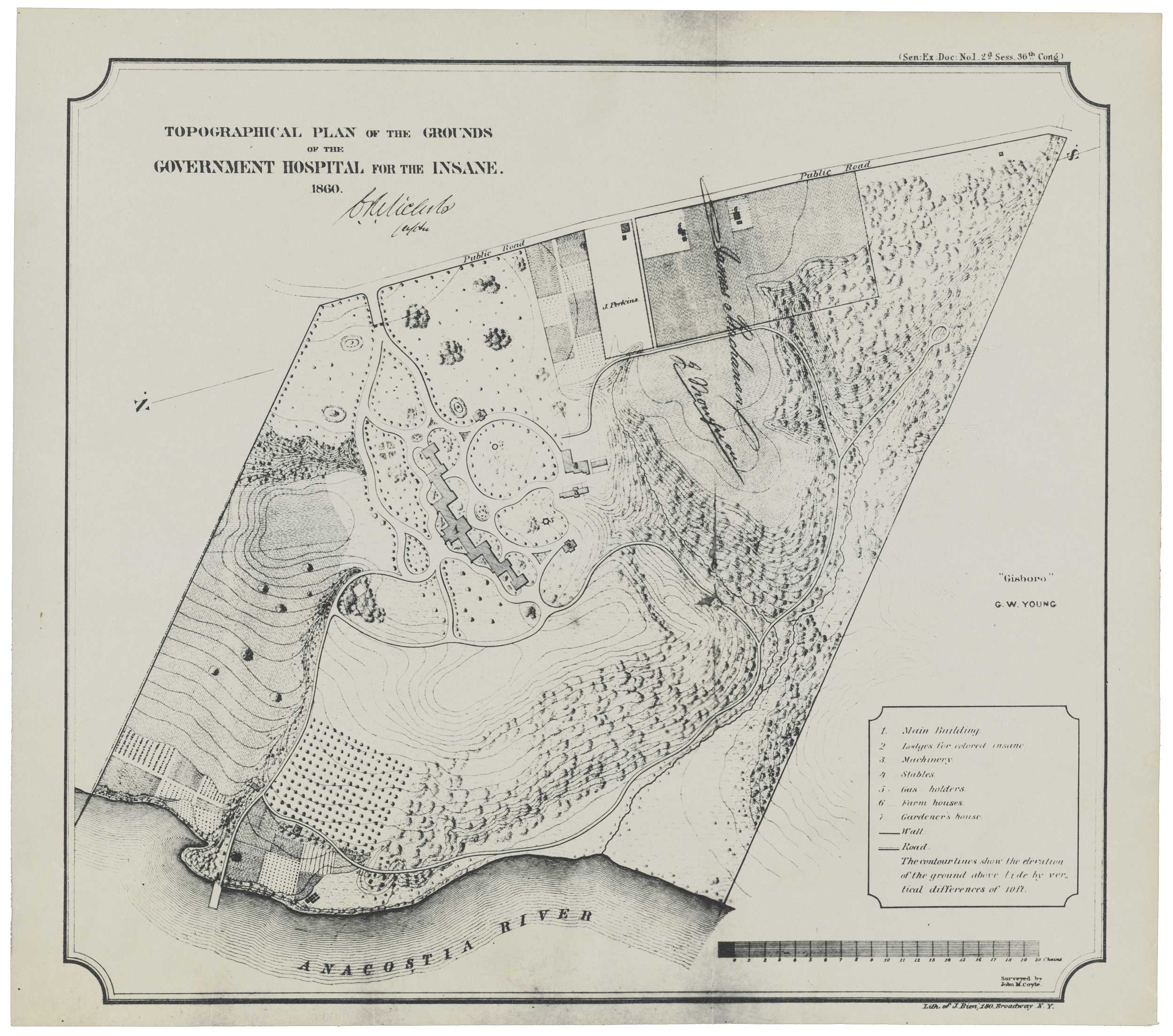

In 2017, I curated an exhibition at the National Building Museum that covered many aspects of that “long and troubled history.” Though that is certainly not an outlandish or particularly unfair characterization, it always is a sticking point with me when stories about the hospital emphasize the troubles the institution has faced, often to the exclusion of anything else. In fact, as always, the real story is more complicated. When St. Elizabeths was founded in 1855, its creators had in mind the most cutting-edge, healthful institution possible. Infamous mental health crusader Dorothea Dix lobbied Congress and the White House, as she did with state legislatures up and down the East Coast, for funding to open a hospital to care for vulnerable people who had been so often cast aside or mistreated at jails and prisons. The hospital opened as part of a national movement called “moral treatment,” a therapy plan that emphasized, as some of its most important tenets, the primacy of fresh air and outdoor exercise for patients.

I keep thinking about moral treatment as we round the bend into month 3 of stay-at-home orders, headed toward a completely new way of existing in the world. Before I start to say nice things about this certainly problematic 19th century movement, let me stipulate: It is true that the originating idea was to make sure patients received ethical care without the barbaric customs that came before. However, it was from the get-go a patriarchal imagining, with one class of people determining what was “best” for another. The most healthful parts about the treatment were often reserved only for white patients. It was stigmatizing, patronizing, and ultimately short-lived in the history of psychiatric treatment. Part of the reason it didn’t last was its inefficiency in dealing with the vast numbers of people who needed mental health care. The treatment plan required hospitals to keep the number of patients fairly low, to facilitate the movement of people and air through the complex. At St. Elizabeths, overcrowding, the encroaching Civil War, and lack of funding precluded the hospital staff from truly implementing the techniques. So, even where some of the ideas may have “worked” to make some patients more comfortable, and certainly less traumatized, than what had come before, most of the system was not ever truly implemented.

Moral treatment, though, had an outsize and fundamental role in the design of the architecture and landscape of mental health hospitals nationwide (worldwide, really) in the mid-19th century. One of the easiest ways to see the values of this movement in the architecture is to understand why the Center Building at St. Elizabeths and other hospitals like it were constructed with bird-in-fight V-shaped wings. Each patient room had windows to take advantage of the healthful properties of fresh air. Known as “Kirkbride buildings,” these structures took their pattern from the same source, mental health hospital advocate Thomas S. Kirkbride. Another way to read the values into the architecture, of course, is to note that the Center Building was constructed for white patients; African American patient buildings did not have this feature, but rather regular dormitory-style construction. The fresh-air treatment—again, focused on the white patients, especially men who had more freedom to walk around the hospital campus—also dug its way into the landscape design, with pathways and “summer houses,” gazebos with benches providing opportunities for catching a breeze or some shade. The siting of the hospital—on a bluff overlooking the city, away from noxious urban fumes—was meant as a way for the landscape itself to provide healthful attributes.

What can moral treatment offer us today? I think some of the values are certainly still resonant, including the instinct to literally build access to exercise and fresh air into the architecture and landscape of our communities. As we’ve seen of late, the freedom to be outside can certainly be contentious. For some people, for whom the great outdoors is always freely accessible on a one-to-one, daily basis—that is, they can open their windows, or simply step outside and walk for miles without encountering crowds—fresh air is easier to access. In other cases, whether in urban settings, or in apartment buildings or group housing, there are more obstacles. Crowded stairwells and elevators, sidewalks doubling as trash and recycling-bin resting places, or pathways too narrow for people to pass one another at all, let alone 6 feet apart. In many areas, streets are still busy enough with cars that they can’t be used for zig-zagging past neighbors and dogs and bikes and joggers and kids on scooters. And this all assumes the freedom, and the time, to move around. Incarcerated people lack the ability to even go outside on their own and have no open windows or easy access to safe ways to exercise.

The discrepancies in how our built environment creates different and inequitable access points to fresh air are obvious. Solutions are perhaps less obvious, though some cities have gotten creative. In many areas, including cities and inner-ring suburbs like mine, governments have closed roads to cars to facilitate exercise and fresh air for residents. Opening beaches and parks has been sporadic and controversial, with some praising the wide-open sand as a public amenity conducive to social distancing, and others condemning those who are seen as less compliant with rules to wear masks and who lack the common sense or interest to stay away from others. Our built environment is not prepared for social distancing, and it does not offer fresh-air equity. Showcased instead is the insufficiency and inaccessibility of our parks and recreation landscapes for so many people in so many places.

Fresh air: still a contested asset.

In the 19th century, fresh air was a commodity that Dorothea Dix tried to bring to people she saw as unable to advocate for themselves. She famously said of her patients, “If I am alone, they are abandoned.” One might argue that at this point in our coronavirus-altered timeline we are all alone—though that, too, is unevenly distributed. But Dorothea Dix wasn’t talking in generalities. I read her words to mean that if she were alone in fighting for the disenfranchised, vulnerable people with mental illness, then they would be abandoned. And unfortunately, as sickness and death tolls continue to rise at St. Elizabeths and at other institutional settings—mental health hospitals, prisons, migrant detention, jails, nursing homes, and juvenile detention centers—her words seem more prescient than ever.

One of the central ideas of moral treatment is that we are all responsible for one another. As we rebuild, I hope we can remember that we must be creative and insightful in thinking of how the built environment itself must be part of how we change. St. Elizabeths’ “long and troubled history” reminds us that our buildings and landscapes reveal deep inequities, but also perhaps a way forward toward some safely shared, shaded paths to the future.

Other Essays in This Series

• The Empty Parking Garage

• Kress at the Border

• This Was the Day

• A Memorial for This Moment