By Nancy Bateman and Laura Hicken, Registrars

The main goal of the collections department at the National Building Museum is to help preserve our artifact collections so they can be researched, exhibited and available for generations to come. The majority of our preservation efforts involve simply storing the materials in a safe way: the entire collection is kept in secure, alarmed, climate controlled rooms and individual objects are stored in acid free folders, boxes and cabinets, away from light and dust. We limit how often an object is moved or touched and when a drawing, photograph or artifact must be handled, we wear gloves to prevent oils on our hands from damaging it.

However, many objects require more than just safe storage and as we come across “problem” artifacts in the collection, we have some simple methods that can help prevent an object from deteriorating and make it more accessible to the public. Here are four preservation conundrums that we’ve encountered recently and the steps we took to improve the condition of objects in our care.

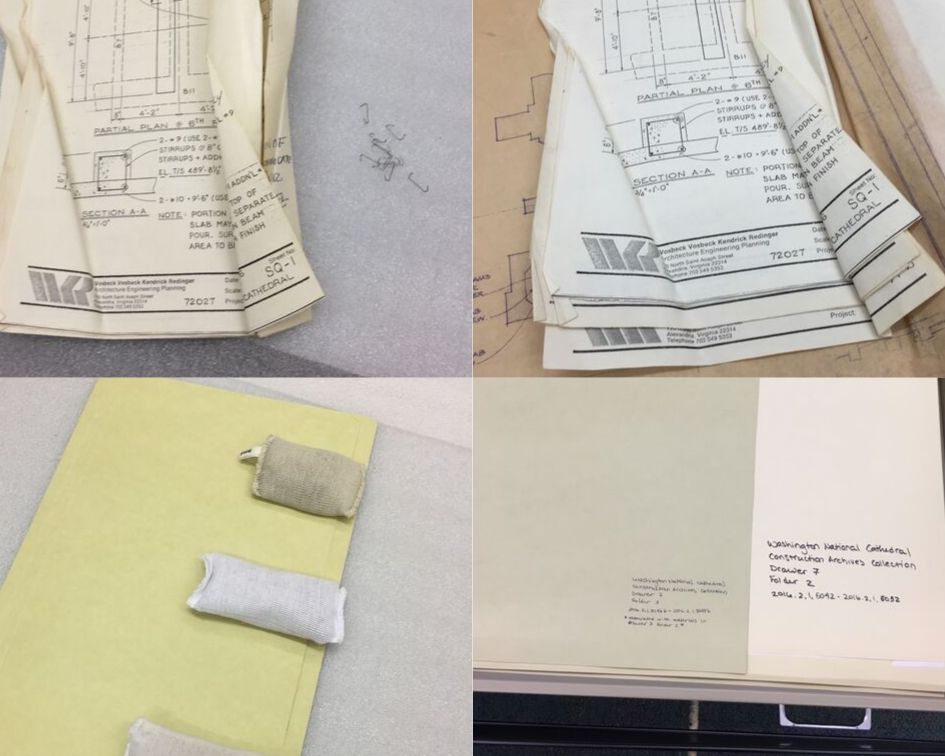

Removing staples, paperclips and other fasteners from paper materials:

From the Washington National Cathedral Construction Archives Collection, these documents were stapled to a Southwest Tower Floor Framing Plan from the 1970’s. The documents refer to the drawing and add important details and context so we wanted to keep them connected to the drawing but need to make some changes. The (many) staples were oxidizing causing stains to the paper, they were also creating larger tears every time the drawing was moved as well as scraping against any drawings below. The staples were slowly and carefully removed to not cause further tearing. Then the very creased documents were smoothed out and weighted down for a week to flatten them. Once they were reasonably smooth again we were able to scan the documents so that they could be associated with the drawings digital file. The documents were then stored in a separate folder but in the same drawer as the drawing so that they would be easily found together in future.

Cleaning decorative plaster:

From the Giannetti Studios Decorative Plaster Collection, this plaster lion head was covered in dust and other debris when it arrived at the Museum. The lion head and sixteen other examples of plaster architectural elements are new acquisitions that came to us directly from the studio and workshop in which they were made and stored for decades. The dust on the pieces was causing discoloration of the plaster, preventing us from seeing the details in the carvings and also was starting to spread around our storage room, so they all needed to be cleaned. The plaster is soft and easily scratched so we had to be extra careful when cleaning it. We started by loosening the dust by lightly brushing the pieces with a soft, clean paintbrush, being extra careful not to scratch the plaster with the metal fastener on the brush between the bristles and the handle. Then we took our small, low suction, artifact only vacuum and slowly suctioned up the dust by brushing it toward the hose nozzle. Heavily soiled areas required a second pass of brushing and vacuuming but overall we were able to get all of the pieces cleaned in one afternoon. Twelve of the pieces, including this handsome lion, will go on display in our new Visitor Center. They’ll be in sealed cases so no additional dust can accumulate on them in the future!

Removing tracing paper drawings taped to fiber board:

From the Washington National Cathedral Construction Archives Collection, this original color pencil on tracing paper rendering of the planned Canon’s Residence from 1939 was taped to high acid fiberboard. We actually got lucky with this drawing, as many beautiful art drawings from the Collection have been heavily glued to high acid cardboard and fiberboard and we have no way of safely removing the original drawing. This particular drawing was adhered using tape, and only a small amount around the edges. The 80 year old tape had almost completely dried out, meaning that with enough care, patience, and a very thin bone folder, it was able to be completely removed without causing any additional harm to the drawing. The tape and fiber board contained no information and provided no additional context to the drawing and could be disposed of, while the drawing could be scanned and tucked safely in its new folder.

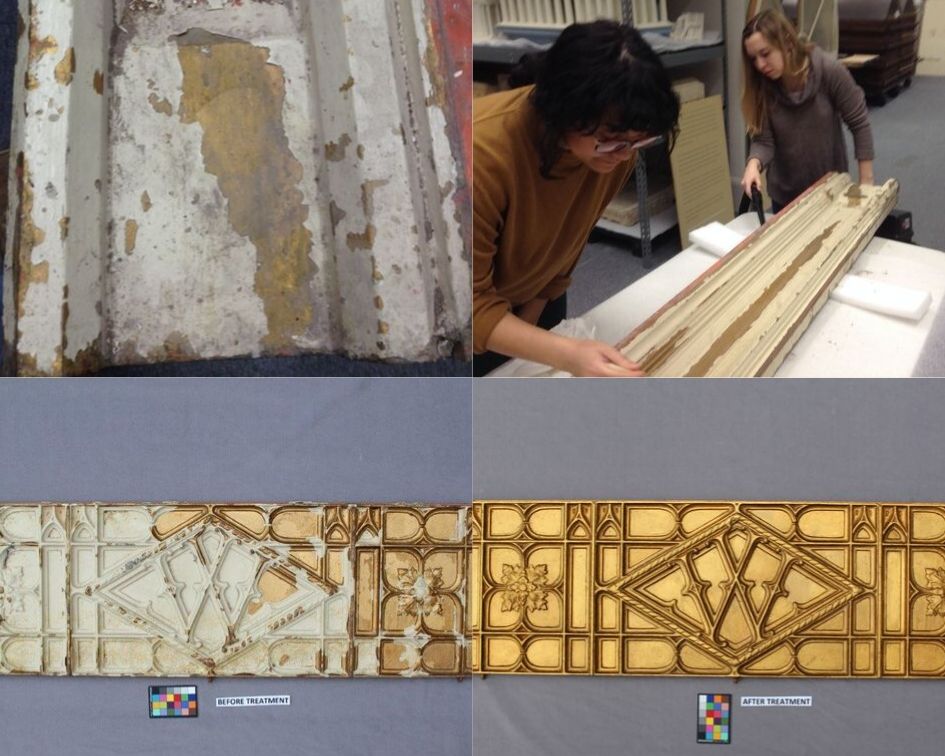

Cleaning and Conserving a Metal Elevator Surround:

From the Woolworth Collection, this metal elevator surround was removed from the Woolworth Building in New York during its recent renovation and was donated to the Museum in 2018. Consisting of 5 parts, the elevator surround was repeatedly painted and repainted for over 100 years while it was in use and then sat in a construction and restoration zone for months before it was finally transferred to the Museum. As a result, the original design, paint and reliefs were buried under layers of paint, dust, and other construction debris particulates. When the surround first arrived at the Museum we dusted it with similar techniques as the plaster clean up – light brushing and vacuuming. However, the surround needed extensive paint removal and restoration to return it to its former glory, which we knew was beyond our abilities and would require the skills of a professional conservator. In preparation for part of the surround to go on display in our Visitor Center, objects conservator Catharine Valentour cleaned the piece, removed the excess layers of paint, inpainted the spots where the original paint had worn off and then covered the entire piece in a gold gilt wax to protect it from further damage. It warms our hearts to see a piece of American architectural history salvaged, restored and soon available for all the public to see again!