Grades 6-12

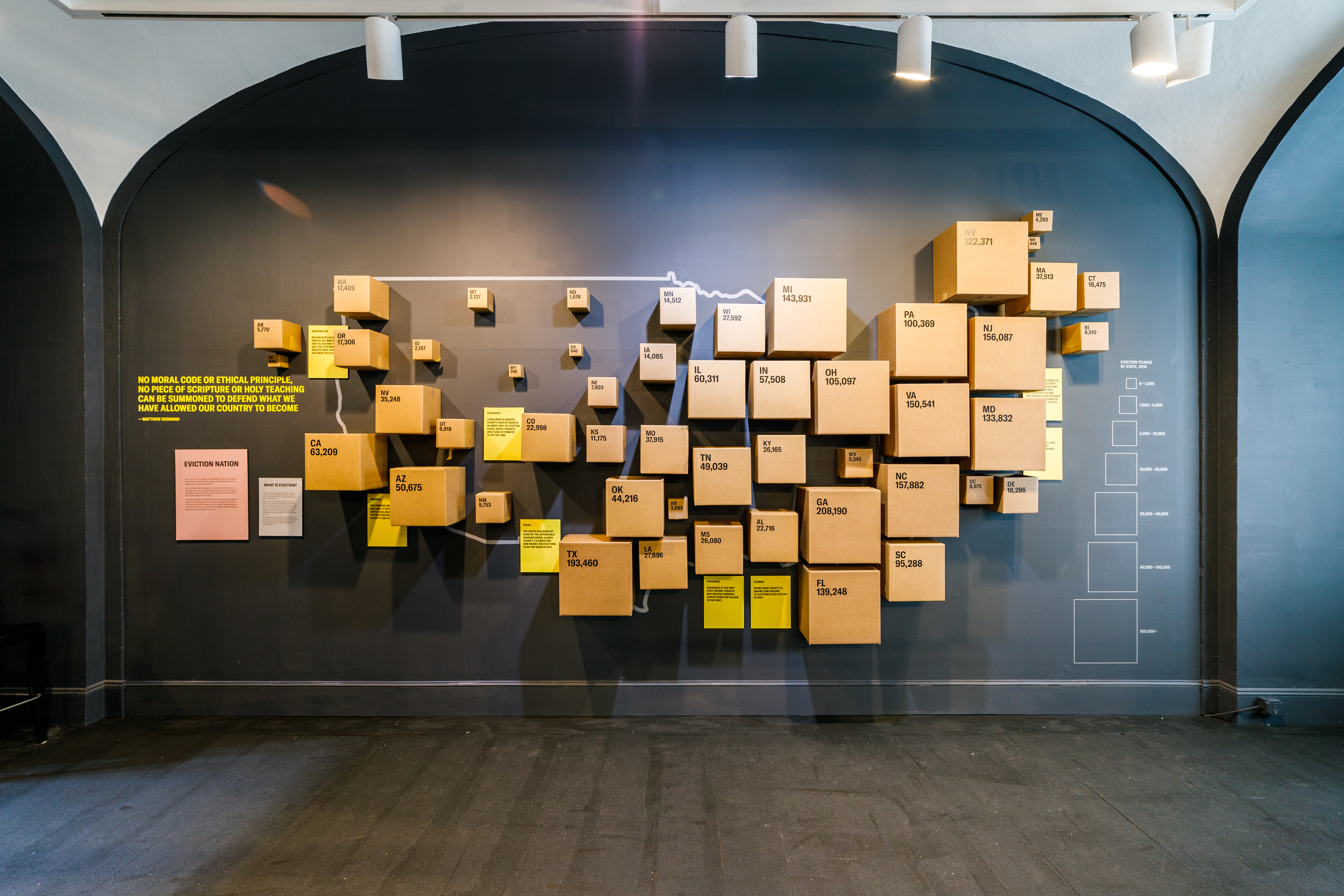

Eviction has become a crisis that affects every community across the country. The Museum worked with sociologist and author Matthew Desmond to create an exhibition based on his book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, and share his research and the scale of the problem of eviction. This teacher guide, made in collaboration with the Interactivity Foundation, provides teachers with resources and a structure to analyze, discuss, and imagine solutions to the eviction crisis and similarly complex issues with their students.

Purpose of the Guide

Eviction has become a national crisis. These are issues that everyone, including students, is dealing with right now in their cities or towns, communities, or personal lives. The National Building Museum worked on this teaching guide with the Interactivity Foundation because of its expertise in facilitating small group dialogues around important policy issues.

By raising awareness of the scale and prevalence of the issue of eviction, the Museum aims to inspire people to raise their voices to address housing insecurity in their own neighborhoods and cities. Equipping students with the ability to break down complex problems, discuss nuance, and integrate new information and opinions will lead to more-informed citizens who can work to solve the growing separation between the built environments of the rich and the poor, along with other pressing societal challenges.

How to Use This Guide

The purpose of the dialogue is for the participants to increase their understanding of eviction as a topic of societal concern, engage with peers to generate alternative ways to address eviction, and learn and apply skills for open collaborative inquiry.

It is not a debate. Participants are not trying to reach a consensus or find the one right answer. A successful dialogue will flow organically rather than marching through a set progression. For this reason, it is important to be flexible in adapting the following material to the teacher’s curriculum goals and to the students’ interests in the topic. The dialogue will likely take multiple class sessions to provide ample opportunity to explore eviction, discuss the complexity of the topic, and collaboratively propose ways to address the issue.

This dialogue format often is for small-group discussions of 10–12 participants, although it can be adapted to use with a large group or class facilitated by the instructor. The role of the teacher in this setting is to facilitate and help make connections between the students and redirect the conversation if it stalls, not to lead the dialogue or insert their own opinions and thoughts.

Heading into the dialogue, be aware that some participants may have experienced the trauma of eviction and housing insecurity. If possible, check with school social workers or guidance counselors to help guide your facilitation of a dialogue about this topic.

As students discuss and share about the topic, record their thoughts and the connections, disagreements, or ideas they have. This allows the facilitator to check for understanding, pace the conversation, and have a reference for each part of the dialogue as it proceeds. These are an internal resource for the students and should not be shared outside the classroom.

Learn more about tips for facilitating a dialogue with the Interactivity Foundation.

This information is adapted from the National Building Museum’s 2018 exhibition Evicted, which focused specifically on court-ordered evictions in the private housing market.

Causes and Effects

Eviction, the forced legal process of removing a tenant from a residence, has reached crisis levels in America. What once was a relatively rare occurrence now threatens more than 11 million Americans, with poor, renting families bearing the worst of it. The rise in evictions stems from three problems that have surfaced in the past 20–30 years.

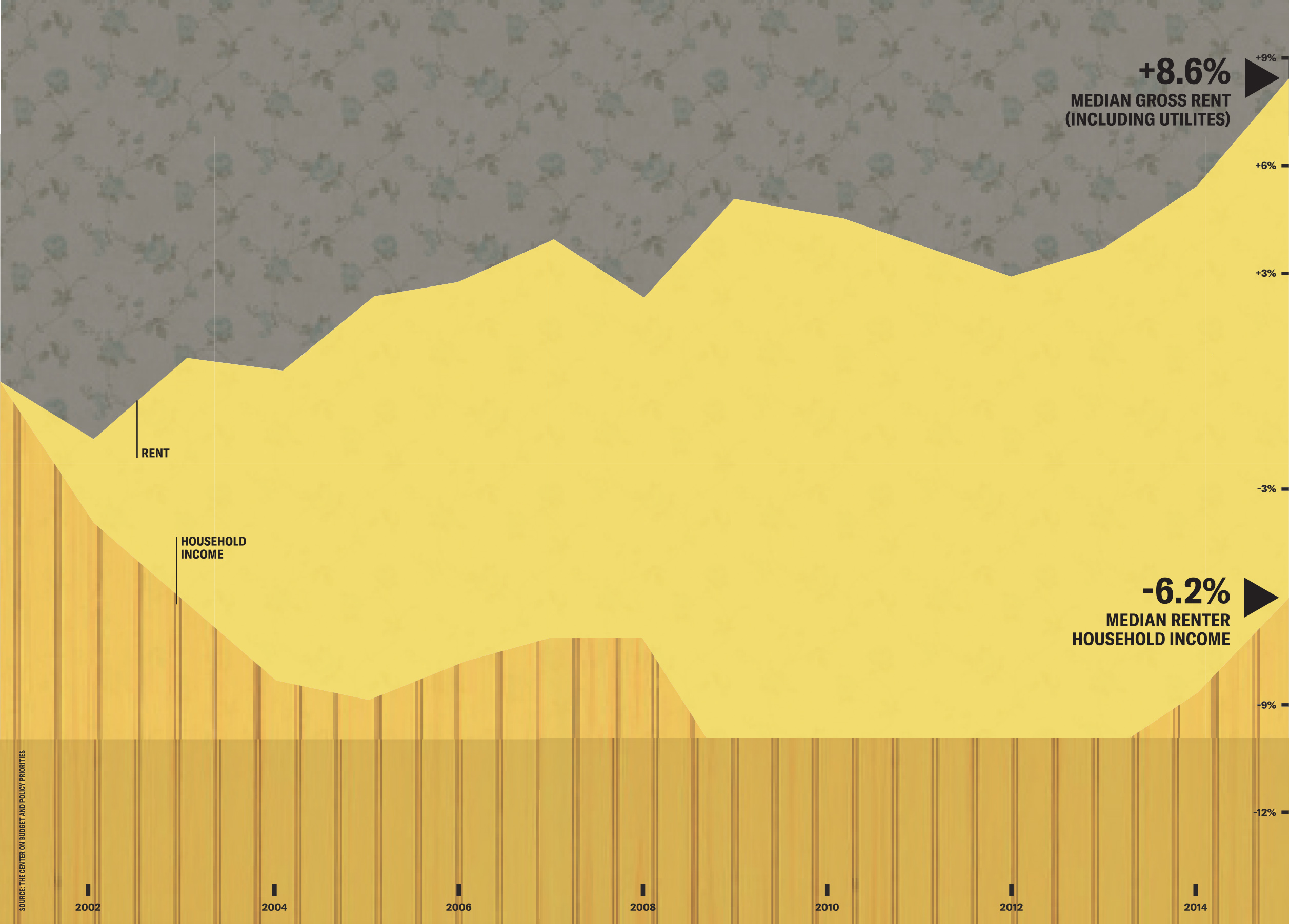

Incomes for renting families have fallen or stagnated.

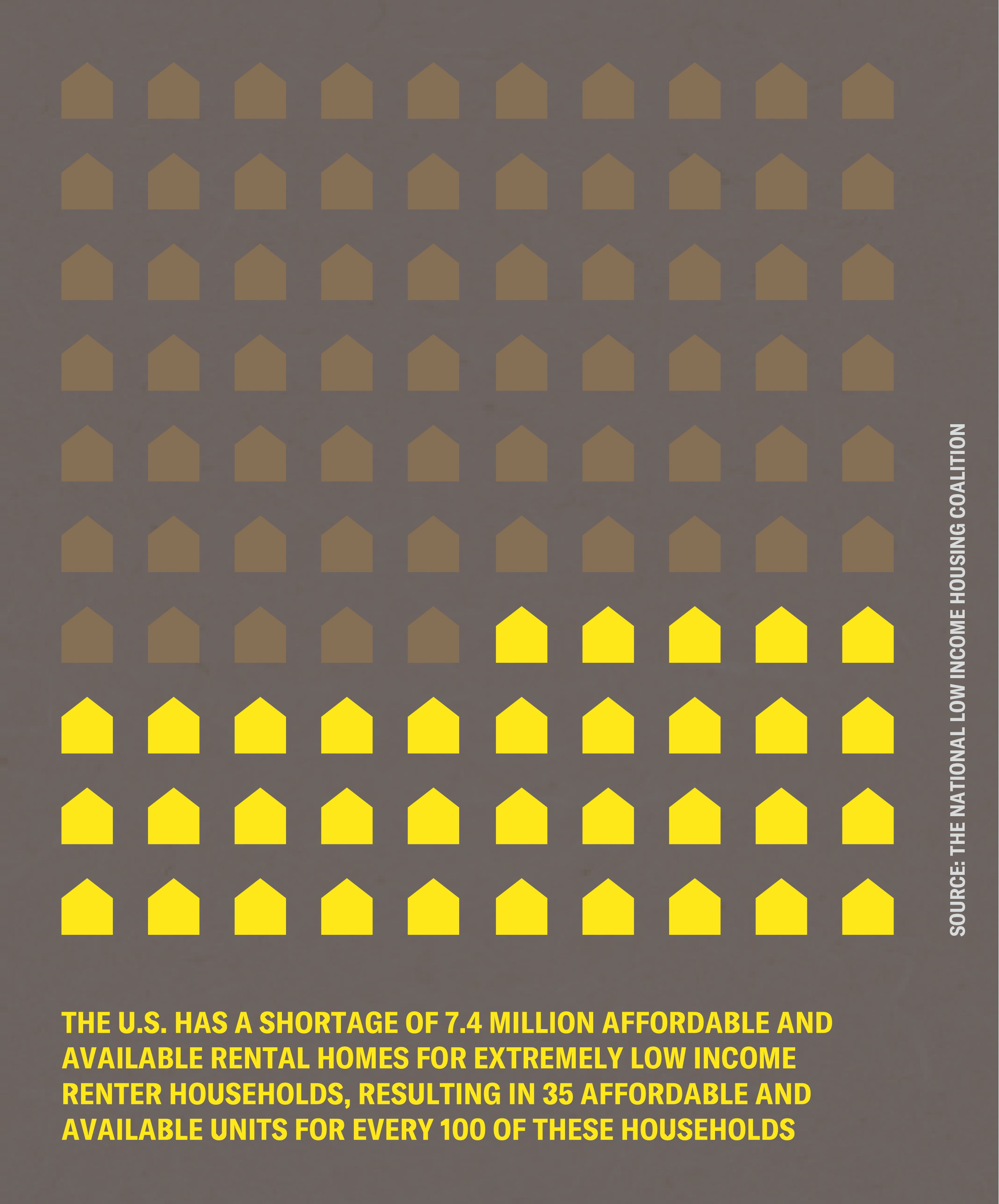

The eviction crisis has revealed a stunning lack of affordable housing across the country. In 2017, a full-time worker earning minimum wage could afford a one-bedroom apartment in only 12 U.S. counties. In other words, low-income Americans do not—and cannot—earn enough money to pay the rent in the vast majority of jurisdictions across the country. This leads poorer renters to housing further away from jobs and opportunities.

Housing costs, including utilities and rent, continue to rise.

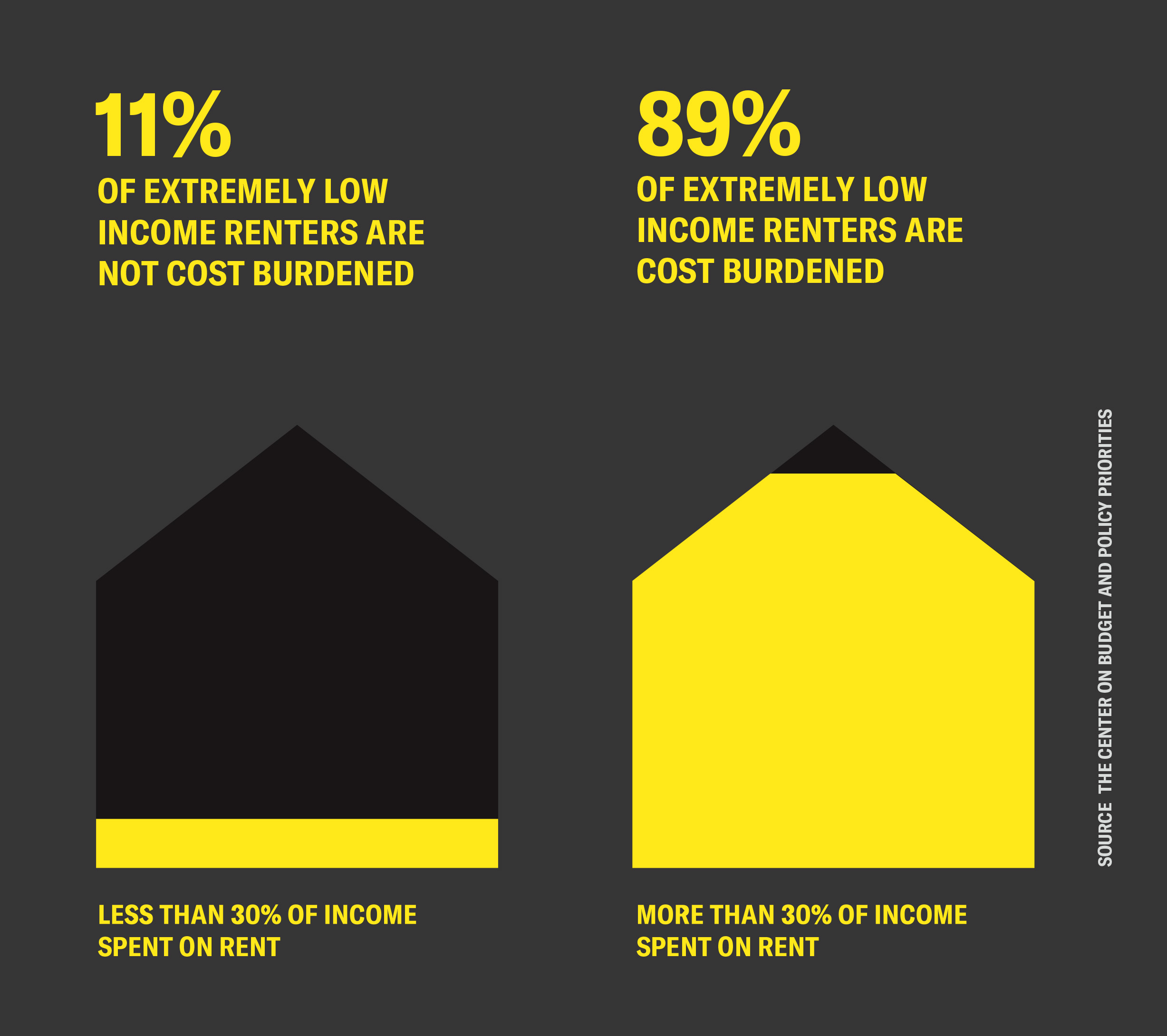

Federal guidelines have indicated for more than 80 years that households should not spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Without government assistance, extremely low-income families end up paying far too much of their income on housing. Today, because of rising housing costs, the majority of poor families spend more than 50% of their income on rent. This leaves very little for school field trips, medicine, food, clothing, or emergencies.

The federal government has not stepped in to help fill the gap.

Current federal and state commitment to housing assistance does not begin to cover the millions of low-income Americans who need help paying for a place to live. In 2015, the federal government spent $29.9 billion on Section 8, which gives vouchers for low-income renters. This is less than half the amount spent on the mortgage interest deduction, for example, which benefits high-income households. Additionally, an eviction can make tenants illegible for the very services and programs they need to secure housing.

Eviction can be a cause rather than a result of poverty. Housing instability can lead to problems at work and school, health issues, and community disengagement for children and families. Adults and children who have gone through an eviction are more likely to suffer from depression and other mental health challenges, and experience worse physical health than their counterparts with stable housing.

In addition, frequent moves can wreak havoc on health plans and relationships with doctors for those with chronic illness. Changing schools means that students may have difficulty developing relationships with counselors or teachers. They may struggle to keep up with different curricula. Even if evicted students somehow avoid changing schools, they face higher stress levels. Job performance problems and even job loss can be traced directly to extreme stress caused by eviction, including hours lost to the legal process and finding a new place to live and longer commute times to jobs from the next round of housing.

Who Plays a Role in Eviction?

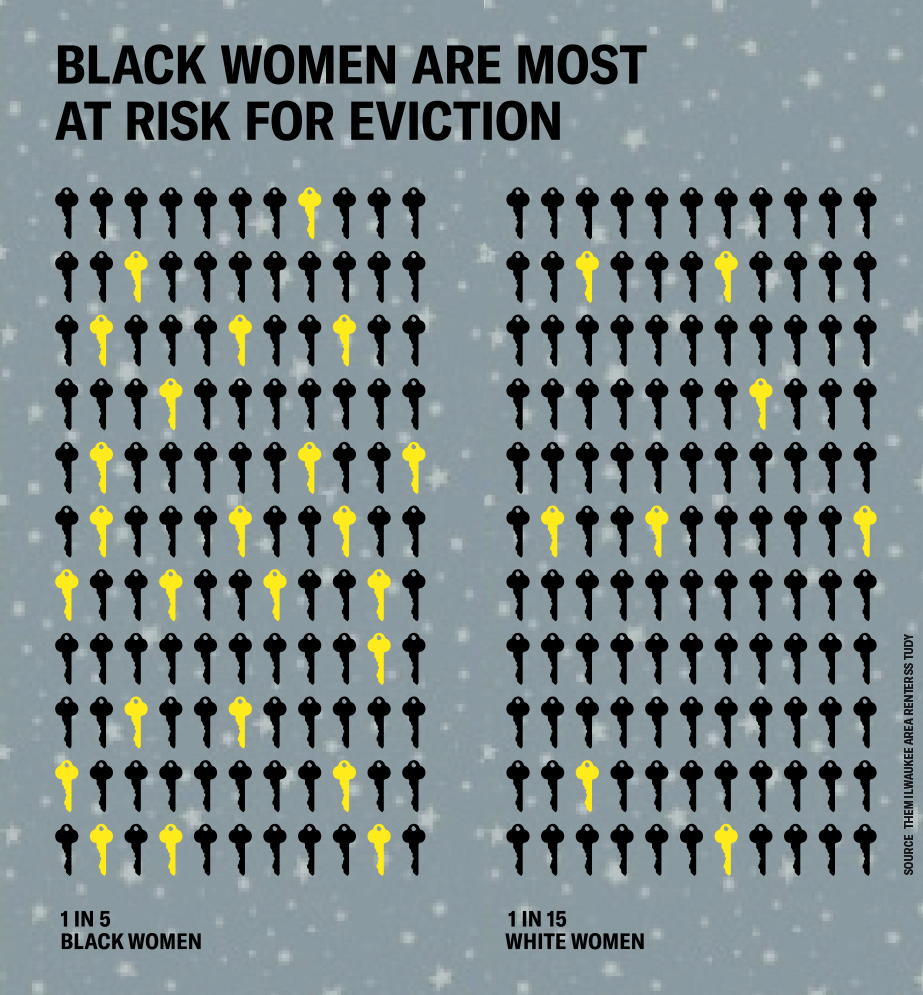

Tenants: Many low-income renters are permanently in the rental market and will never own a home. The number of low-income renter households most at risk for eviction continues to grow. Once a family experiences hard times leading to an eviction, it can be difficult to find a landlord or rental company willing to rent to them, continuing a spiral of downward mobility. In 2017, almost 2.5 million American households faced court-ordered eviction. Even more people lived with the threat of being forcibly removed from their homes, but managed to find another living situation before the final knock on the door. Eviction is more common for African American single mothers than for all other groups. In fact, poor single mothers of all races are particularly at risk. Children often expose families to eviction instead of protecting them, as landlords often see youth as disruptive.

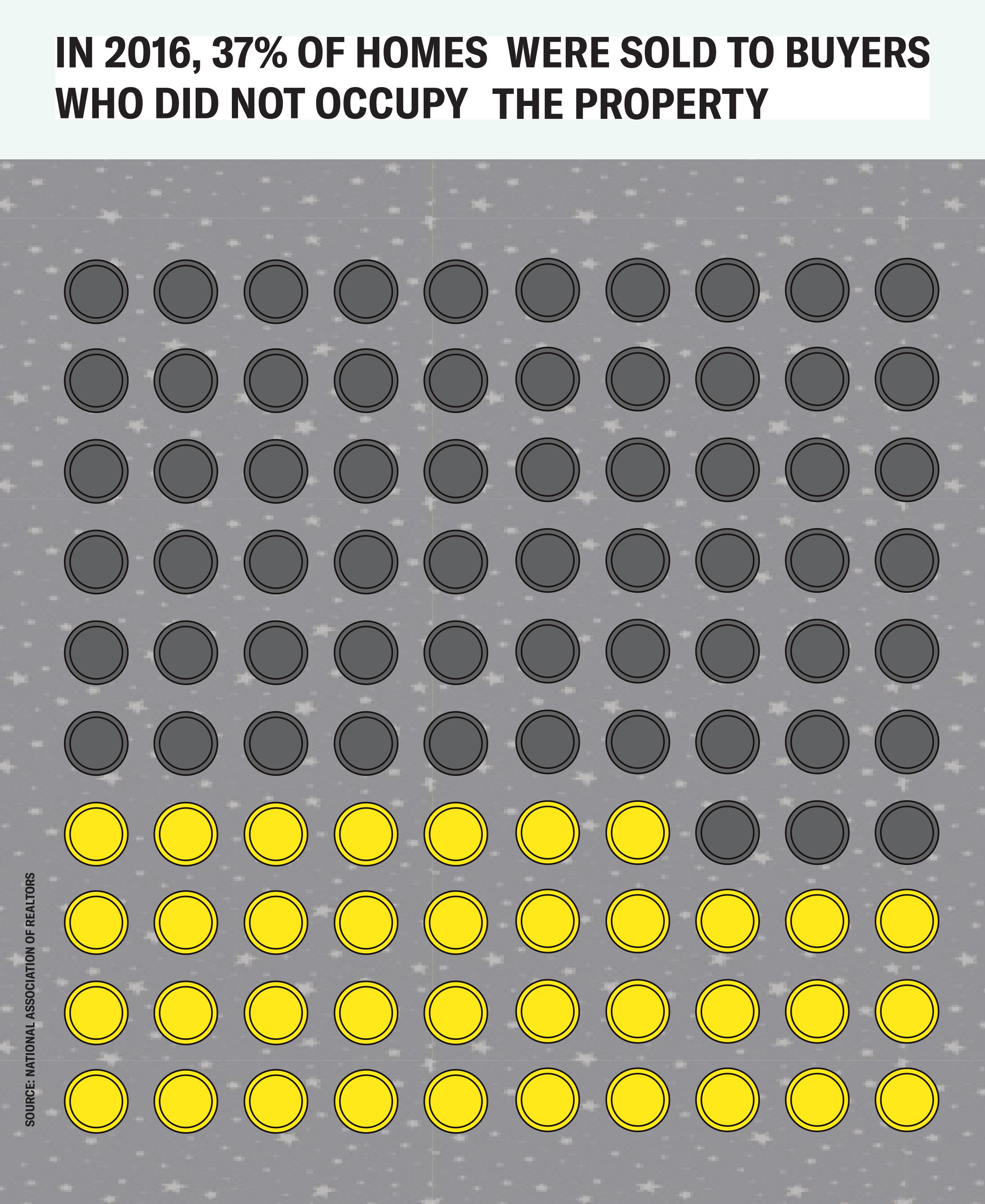

Landlords: In 2016, 37% of homes were sold to buyers who did not occupy the property. Landlords are playing a new and significant role in the housing market. “Slumlords” in poor neighborhoods can often make more money than they could in more upscale markets. Sometimes they will raise rents in anticipation of incurring losses. They may also save by forgoing upkeep and maintenance.

Court system and lawyers: The housing court system can be complicated. Unlike in a criminal case, tenants in eviction cases are not guaranteed legal representation. Most landlords can afford counsel, which gives them the advantage over tenants in navigating the court system. Judges gavel through cases with little time to consider individual circumstances. Taking time off work or the hassle of traveling to court often means that tenants are not even present when their case is decided.

Law enforcement: Once an eviction starts, sheriffs or marshals are present to serve the eviction notice. Many low-income renters also risk eviction if they call the police to report a crime in their home. Nuisance ordinances, the law in many cities and states nationwide, allow—or even mandate—eviction when the police are called to the property too often.

Moving companies and storage facilities: Whether tenants are home or not during an eviction, their possessions will be removed from the house by a moving company. In some jurisdictions, tenants can choose to have their possessions brought to a storage facility, but that is often too expensive or time consuming to be practical.

Additional Resources

Learn more about eviction, housing instability, actions to take in your own community, and national organizations that are working on this issue.

Suggested Dialogue Outline

- Explore background information

- Set up group agreement: 10 minutes

- Warm-up: 10 minutes

- Exploring different aspects of eviction: 30–45 minutes

- Generating possibilities: 30–45 minutes

Explore Background Resources on the Eviction Crisis

The background information, data visualizations, and other resources are provided for teachers and students to gain an understanding of the system of eviction. The downloadable version of the teacher guide contains data, quotes, and information from the Evicted exhibition that can be shared with students to learn more about the causes and effects of eviction and the people involved in the process. Resources like the Eviction Lab allow students to explore eviction data and rates in their own states and communities.

Set Up Group Agreement

When students set up their own ground rules or basic agreements for a dialogue, they can take more ownership of the process. The Interactivity Foundation suggests the following elements for a successful dialogue:

- Take turns.

- Stay on track.

- Listen to each other.

- Be open to each other’s ideas and build on them.

- Be ourselves and imagine other perspectives, including people who aren’t present.

- Be generous with each other and the ideas that come up.

- Help each other explore or clarify ideas to uncover complexity.

- Separate the idea from the person.

- Be bold and going deep into the issues.

- Consider all ideas.

- Bring up innovative ideas, even if they seem implausible.

- Question assumptions and look for root causes.

Warm-Up

What makes a home a home? What does “home” mean to you?

This question is intended to help a conversation get started and to create a sense of personal connection to the discussion topic. As students share, record their answers visibly so everyone can see.

Explore Eviction

Below are suggested questions to select for engaging in dialogue on different dimensions of eviction. Facilitators should not try to work through all of these questions. Some groups might only work through two or three, others might cover four to six. The questions the facilitators ask will arise from the curriculum connections they are making and might shift as the participants take the dialogue in the direction that interests them. As with the warm-up, record responses as you continue the dialogue.

Questions to start the dialogue:

- What questions do you have about eviction?

- What surprised you about the background information we researched? What are you wondering?

- Who are the people (or groups of people) involved in the system of eviction?

- What are some of the different factors that lead to people being be evicted or losing their homes?

Questions to explore complexity of eviction:

- What values seem important to consider when thinking about housing and the loss of housing?

- What responsibilities are there when it comes to housing and eviction? Who has these responsibilities?

- What rights do people have, or should they have, when it comes to housing and eviction? Who has these rights?

- Whose interests or needs should be considered when thinking about eviction? What are some different perspectives to consider (tenants, landlords, business community, and government)?

Questions to synthesize points of view:

- What are some of the root causes (e.g., wages not growing) that we discussed or researched that we might have to address if we’re going to solve eviction?

- What goals might we have as individuals, a community, or as a society when it comes to eviction and housing?

- What are the big questions about eviction and housing that we have to answer as a society/city/neighborhood/community?

Consider using other methods to break up the spoken conversation or to make the dialogue visible—such as sticky note reflections, personal journaling and sharing out, or collaborative mind maps (silent brainstorms)—as a way to discuss and share with each other. This will allow less vocal participants the chance to respond and be engaged in the dialogue with their peers.

Generate Possibilities

The following dialogue and activity prompts present different ways to help students imagine alternative possibilities for addressing eviction on a societal, community, or personal level. These build on the previous dialogues and can help students imagine a positive way forward through the eviction crisis. Ideally, there is time between the previous section of dialogue and this portion to allow students to reflect and digest what they discussed and heard. Facilitators do not need to complete all of these prompts.

Prompt: History of the Future Brainstorming

Imagine a future where the problem of eviction is “solved” or minimized (it’s up to your students to imagine what that might mean).

- What does society/our city/our neighborhood look like with little or no eviction? How do we handle issues surrounding economic insecurity and housing?

- How did we get to this situation? What steps occurred in history that led us to this new future from where we are now?

- What actions could be take right now to move our society/ city/ neighborhood towards that future?

Prompt: Using Metaphors to Envision Possibilities

Generate different metaphors (Housing is… ; Home is…; etc.) to express what housing means to your students.

- Write or make drawings of these metaphors. What values do these metaphors suggest that would shape how we deal with eviction? Example: “Home is a warm blanket on a cold day.”

- Take a metaphor for housing and try to build a policy or solution around it that could address the problem of eviction. Example: “If housing is a warm blanket on a cold day, then our policy is to ensure that housing is easily available for the most vulnerable populations.”

- Discuss who would be involved in moving that solution or policy forward (government, businesses, nonprofits, activists, etc.) and what they would do.

Prompt: Dive deeper into solutions for previously discussed questions

Given the goals, values, rights, responsibilities, etc. that you discussed, what are some different ways we could address eviction?

- What would the goal of your solution be in our country/city/neighborhood/school?

- Who would do what (or who would have which responsibilities and rights)?

- What values would shape the solution or policy?

- In a nutshell, how would it work? How would this solution change our society/city/neighborhood/school?

The Evicted Teaching Guide was partially made possible by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Many thanks to Sarah Leavitt, curator of the Evicted exhibition, for her assistance in creating this guide, and Jeff Prudhomme at the Interactivity Foundation for facilitating discussions about the topic of eviction.

Special thanks for the following teachers for their help and feedback to test and improve this guide:

Lauren Brownlee

Lori Crawford

James Ewing

Sean Felix

Chavala Hardy

Heather Maclean

Olivia Shipley

Lisa Sprehn

Lesley Younge