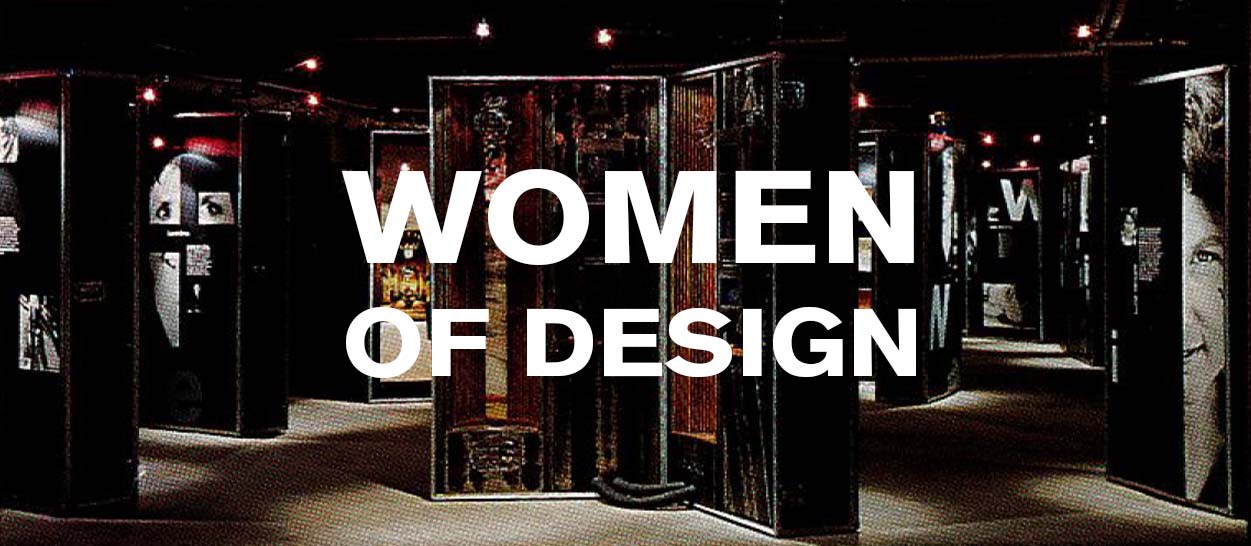

In honor of Women’s History Month, the National Building Museum looks back at the 1993 trunk show highlighting 33 architects and interior designers.

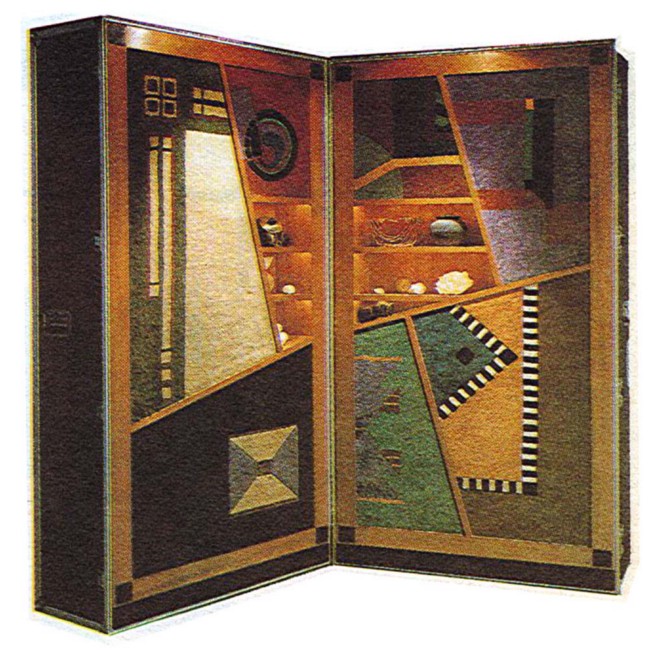

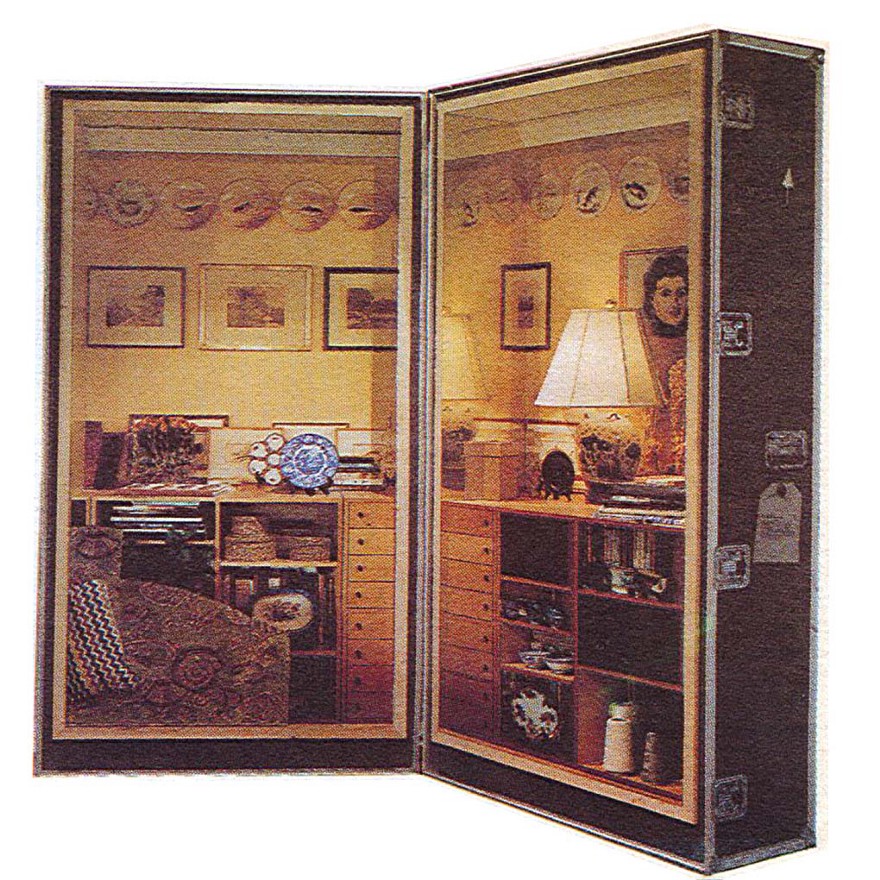

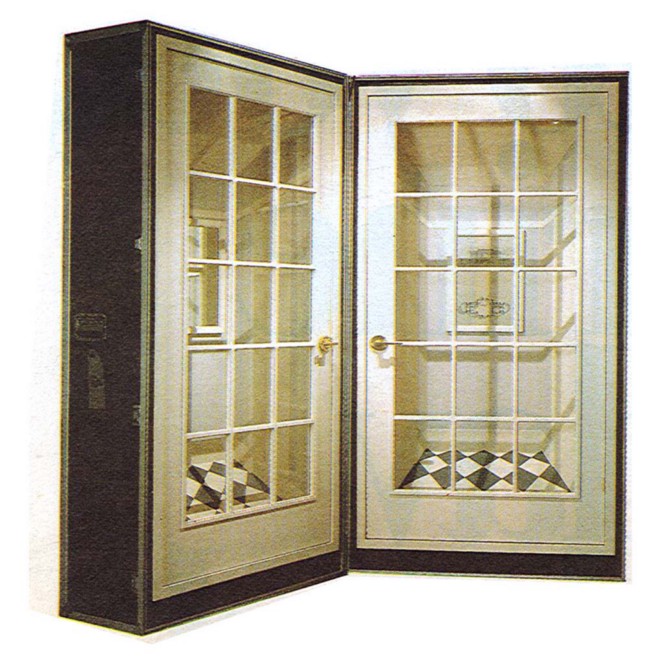

Thirty-three steamer trunks stood on end within the Museum in 1993, each brought to life by an interior designer or architect—all from well-known firms, all of them women, and recognized as the first generation to rise to prominence in a field traditionally dominated by men.

The exhibition originally opened in New York City in October 1992, coinciding with the release of Beverly Russell’s book Women of Design, which provided the original inspiration and exhibition name. Each designer, invited to participate on the basis of their professional achievements and contributions to the architecture and design industries, was provided with a 7-foot-tall steamer trunk, which they designed based on their own interpretation of the exhibition’s theme.

In all, the 33 women took on the design challenge in a vast number of ways, whether as a chance to reflect on their life’s work, an attempt to use the space as a minimalist design challenge, or as an outlet to speak to future generations on the importance of women in the field of architecture and design.

The exhibition’s underlying theme was the celebration of women’s advancement in a field that kept women at arms length throughout much of its history. With the growth of office buildings and increase in travel after World War II, women branched out from redecorating homes to designing important public spaces and began to make their presence felt; where in 1993 women made up only 9 percent of the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) members, women today make up 18 percent of its members.

In a 1993 interview for Women of Design, Lucia Howard, one of the exhibitors, speculated on the growth of women in architecture: “I think the presence of women has grown to the point where the students in some schools are over 50 percent female.”

In that same article in which Howard was interviewed, author Beverly Russell was asked about women’s progress in architecture, responding, “It’s difficult for women architects unless they run their own firms. Many women architects are doing interior design. But they are unable to move forward with their architectural training, and want to retain their own independence.”

This fight for recognition has been routine for women. Marion Mahoney Griffin, employed by Frank Lloyd Wright, was not given due recognition for her Prairie School designs. Today we now know of the extent of her contributions to Wright’s studio work along with her efforts to promote many of his ideas.

Indeed, as time has passed it has become more apparent how women have influenced the built environment, especially as more women enter the field. Later in the same interview with Howard, she went on to say, “In fact, there are so many women coming into the profession that values traditionally associated with women are being taken seriously—like being concerned about the social and psychological characteristics of a space.”

These values that Howard explained could be seen throughout the exhibition, as visitors roamed through the space discovering one trunk after the other.

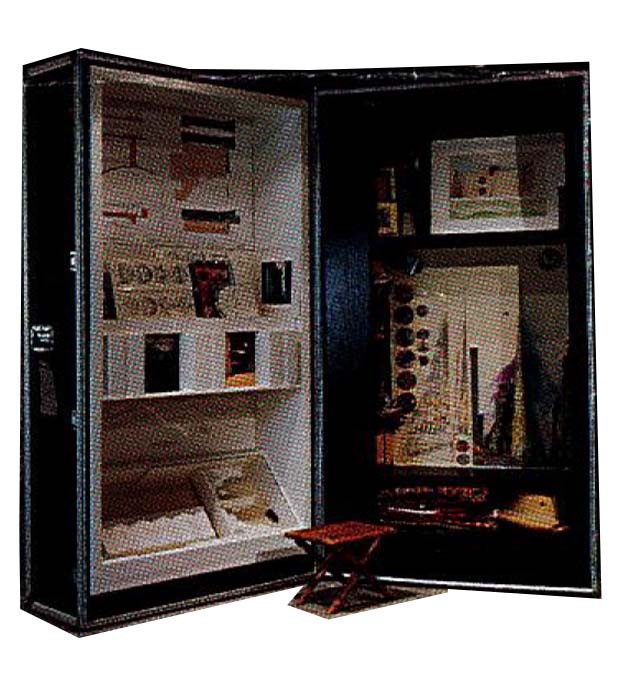

Elizabeth McClintock approached her steamer trunk idea as a design challenge. The trunk was transformed into a kind of mobile home. Opened up, it disclosed a fold-down bed, a counter with recessed sink and a hot plate placed on top, along with cupboards and a reading light.

Margo Grant Walsh chose to use the trunk as a chronicle of her work in the design profession and included photos of past design projects. This work included her contributions as head of interior designers on the Bank of America world headquarters and the interior of Pennzoil Place, one of Houston’s most notable Postmodern buildings. Walsh has gone on to be honored in 2001 with the establishment of the Margo Grant Walsh Professorship in interior architecture, and the Ellis F. Lawrence medal—the highest honor of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts at the University of Oregon.

Carolyn Iu chose a minimalist series of materials from different cultures, coupled with a passionate statement about design’s global aspect and the need for sensitivity to cultural diversity. Iu’s work has taken her from her home in Hong Kong to projects in the Pacific Rim and throughout the continental United States. Iu went on to form Iu & Lewis Design in 1995.

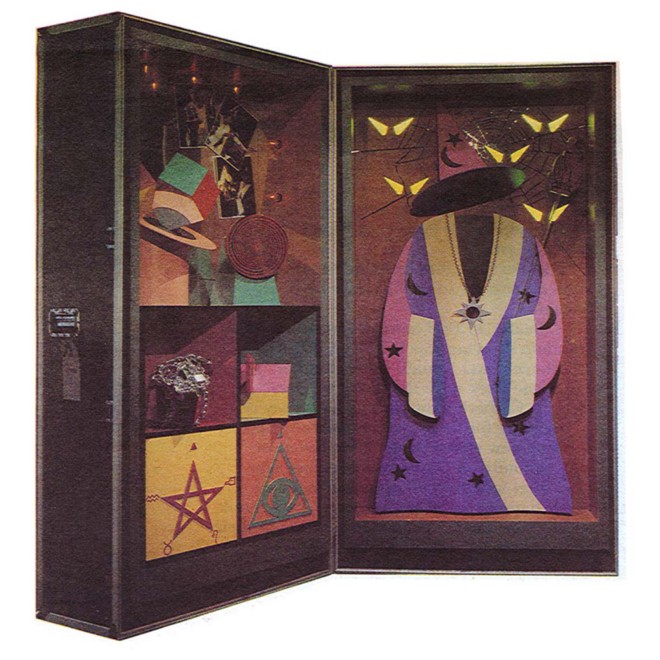

Spes Mekus’ design included a top hat and wand and explored how the designer, using basic elements such as light, color, form, and volume, can surprise and delight the viewer “as if by magic.” Mekus is now one of the principals of Mekus Tanager Inc. and is recognized nationally as one of the design leaders in commercial interior design.

- Phyllis Martin-Veque

- Martha A. Burns

- Margaret McCurry

Clodagh incorporated video images, flickering lights, a working fountain, and a voice-over that starts, “Design incorporates all of the senses.” In 2008, Clodagh celebrated her 25th anniversary as a designer in New York and has been recognized with awards including the Interior Design Hall of Fame.

Another Interior Design Hall of Fame recipient, Trisha Wilson, imagined her trunk as a simulation of an American Passport whose “visa stamps” covered the exterior displaying colorful images of great international hotels, reflecting well on her career focused on high-end hospitality. Wilson has given much of her recent attention to philanthropic efforts for the world’s underserved children, via the Wilson Foundation.

Finally came Frances Halsbrand, who served as Dean of the School of Architecture at the Pratt Institute in New York and was the first woman elected president of the New York Chapter of the AIA. Halsbrand decided to use her trunk to speak to the future, the trunk presented a photo album of female students, the next generation of women designers.

Although it is true today that more women are studying architecture and design, the matter of women actually advancing in the field becomes a bit muddled after academia. In 2016 The L.A. Times reported that although women make up nearly half of all architecture school graduates, only 18 percent of licensed practitioners are women.

The full list of Women of Design Architects is listed below:

- Leslie Armstrong

- Pamela Babey

- Gretchen Bellinger

- Martha Amanda Burns

- Josephine Carmen

- Clodagh

- Karen Daroff

- Lee Foster-Crowder

- Margo Grant

- Carol A. Groh

- Frances Halsbrand, FAIA

- Dorothy Clark Harris

- Kitty Hawks

- Margaret Helfand

- Lucia Howard

- Clara Igonda

- Carolyn Iu

- Naomi Leff

- Debra Lehman-Smith

- Dian Love

- Eva Maddox

- Stephanie Mallis

- Phyllis Martin-Vegue

- Elizabeth McClintock

- Margaret McCurry

- E. Spes Mekus

- Julia F. Monk

- Sylvia Owen

- Rita St. Clair

- Lella Vignelli

- Lynn Wilson

- Trisa Wilson